THE

AGA KHAN TRUST FOR CULTURE

THE

AGA KHAN TRUST FOR CULTURE

PRESS RELEASE

FOR IMMEDIATE

RELEASE

AGA KHAN WELCOMES THE SORBONNE'S NEW SERIES ON ISLAM

The inaugural volume, "L'Egypte Fatimide: son art et son histoire" is launched at the Institut du Monde Arabe

Paris, France—3rd

December, 1999— His Highness the Aga Khan, Imam (spiritual leader) of the

Ismaili Muslims, today expressed the hope that more initiatives such as

well-researched publications, exhibitions and scholarly exchanges by academic

and cultural institutions in the West, "could help deepen public understanding

of Islam and its intellectual and artistic

heritage."

The Aga Khan was attending the formal launch by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC) and the Presses de l'Universite de Paris-Sorbonne of a new series of publications on Islam. The first volume in the series, L'Egypte Fatimide: Son Art et Son Histoire, brings together the contributions of over fifty eminent scholars who participated in an international colloquium on the subject in Paris in May 1998 co-sponsored by AKTC.

Others present at the launch at the Institut du Monde Arabe included the Egyptian Ambassador to France, Mr. Ali Maher El-Sayed as well as representatives from the French government, the diplomatic corps, UNESCO, academia, cultural organisations and the media. Also attending were Prince Amyn Aga Khan (the Aga Khan's younger brother) who is a Director of AKTC and Prince Hussain Aga Khan (the Aga Khan's younger son), who has specific responsibility at the Aga Khan's Secretariat for AKTC's programmatic activities.

Commenting on the inaugural volume, its editor, Marianne Barrucand, Professor of Islamic Art and Archaeology at the Sorbonne said "the art and culture of the Fatimids is the expression of a remarkably tolerant multireligious and multiethnic society, the source of impressive material prosperity and of an unprecedented creative vitality." The Sorbonne's newest series, according to Mme Brigitte Taillebois, Collections Editor at Presses de l'Universite de Paris-Sorbonne, "will bring together in publications of quality, the works of authors already well-established in the field as well as specialists engaged in new areas of research relating to the Islamic world."

Concurrent with the colloquium whose proceedings are set forth in L'Egypte Fatimide: son art et son histoire, the Institut du Monde Arabe had launched a four-month long exhibition entitled "Tresors Fatimides du Caire" which brought together from public and private sources, the largest collection of art and artifacts ever exhibited relating to the Fatimids, a dynasty whose rule extended over two and half centuries across North Africa and parts of the Mediterranean and the Middle East. The collection was subsequently exhibited at the Kunstlerhaus Museum in Vienna, Austria from November 1998 to February 1999.

Mail: P.O.

Box 2049, 1211 Geneva 2, Switzerland Address: 1-3 Avenue de la Paix,

1202 Geneva,

Switzerland

Telephone:

(41.22) 909 72 00 Facsimile: (41.22) 909 72 92 E-mail:

aktc@atge.automail.com

The Aga Khan Trust for Culture, established in 1988 in Geneva, Switzerland, is a private, non-denominational, philanthropic foundation. Recognising that buildings and spaces are physical manifestations of culture in societies, past and present, the Trust seeks to improve the quality of built environments in societies where Muslims have a significant presence. The Trust is a member of the Aga Khan Development Network, a group of private, international development agencies and institutions working to improve living conditions and opportunities in the developing world, particularly in Asia and Africa. The Aga Khan, who is the 49th hereditary Imam (spiritual leader) of the Ismaili Muslims, is directly descended from the Imam-Caliph al Mahdi who established the Fatimid dynasty in North Africa in 909 C.E.

The Aga Khan Trust for Culture is also a founding member of the Association Aga Khan created in France under the Law of 1901. The Association Aga Khan, earlier this year, signed an Accord of Co-operation with France with a view to creating closer linkages in the fields of social, cultural, economic and humanitarian endeavour.

For further information, please contact:

The Aga Khan Trust for Culture

1-3 Avenue de la Paix

1211 Geneva 2,

Switzerland

Telephone: (41.22) 909.7200

Fax: (41.22) 909.7292

E-mail: aktc@akdn.ch

Discovering Cairo in the Footsteps of The Fatimids

Explore Cairo,

the exotic city of the Fatimids, as Paris pays tribute, presenting an exhibition

on this ancient Egyptian civilisation.

By Jean-Claude

Perrier

Photos: Jacques

Denarnaud

The

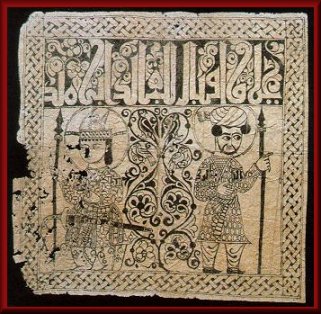

Fatimid Wall

The

Fatimid Wall

The French may have a reputation for being weak on geography and it can sometimes even extend to history, for example the history of Egypt which, when seen from a French point of view, often makes a great leap from the time it was annexed to the Roman Empire by Agustus in 30 BC to the time the Republican armed forces landed in 1798, a key yet brief moment in the country’s history which only lasted three years.

It is almost as if the pharaohs in their mastabas, hypogean underground or pyramids had cast a spell over the country and their descendants.

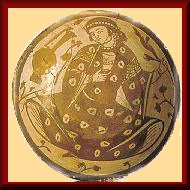

Jewelry

box with scenes from hunt,

Jewelry

box with scenes from hunt,

made of ivory,

11th - 12th century

As the woods cannot be seen for the trees, so ancient Egypt, having risen from past oblivion and in great style since the 19th century with accomplices such as Vivant Denon, Champollion and Mariette, has now cast its shadow over all the intervening civilisations.

Most western travellers, wrapped up in packages by tour-operators, see Cairo as a short stopover, visiting the pyramids, the Gizeh Sphinx, the national museum with the mummies and treasure of Tutankhamen, as a latter day sorting centre for the wonders of the pharaohs of upper and lower Egypt.

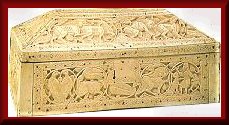

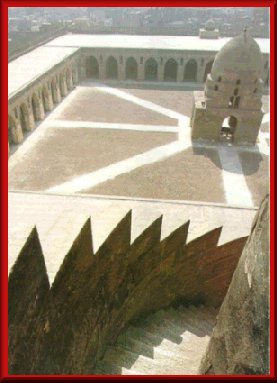

View

from the Citadel

View

from the Citadel

Such an approach is utterly unjust and the exhibition on the Fatimid treasures of Cairo currently being presented at the Insitut du Monde Arabe in Paris is a timely reminder of this. Here is an opportunity to discover and exciting period in the history of Egypt, the time of the Ismaili Shiite caliphs who had travelled from western north Africa and ruled over the country from 969 AD (when Al-Qahira, “The Victorious”, was founded by them) until 1171.

Cairo cannot

be compared to any other city in the world: it is a noisy, colourful, sprawling,

anarchic megalopolis with a population of twelve million, spreading out

into residential suburb which are gradually being swallowed up by the city.

It is the capital of modern Egypt and home to 20% of the country’s population.

Bab-el

Futuh

Bab-el

Futuh

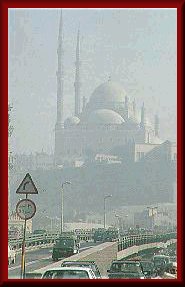

Today, the Fatimid monuments of Cairo are bound by the lines of a large imaginary square, stretching west to the avenue of Port Said (the address of the quite magical and peaceful Islamic Art Museum which has loaned most of the 250 pieces presented in the Paris exhibition), then north and east along a boundary partly marked by a wall with a number of monumental gates, such as Bab El Futuh, and then south as far as the street named Ahmed Maher with the Zuweila gate and the famous bazaar of Khan el Khallili, as well as the grand mosque and university of El Azhar, the leading authority in the Muslim world which was originally founded in 988.

View

from the Mosque of Al-Azhar University

View

from the Mosque of Al-Azhar University

A labyrinth of small, densely populated streets covered in dust or mud, depending on the weather, is home and/or workplace for a vast population. Private dwellings and shops have sprung up in total anarchy, as have mosques and masdrasas (the Koranic schools), similar to the emergence of Christian cathedrals in the middle ages. To avoid getting lost in such chaos, follow the street of El Muizz Din Allah, which runs across the district from north to south. The buildings are often in a poor state of repair, despite recent campaigns to save and restore them; every different architectural period can be seen in a haphazard assortment.

A few hundred meters further on, the visitor walks past the Fatimid wall dating from 1087, a Mamluke mosque (the Mamelukes reigned over Egypt from 1250 to 1517) and a sabil, the fountain beneath a Koranic school dating from the Ottoman period, which preceded the French conquest of the country, the bicentenary of which is being celebrated, albeit controversially, this year.

Cup

of the Princess,

Cup

of the Princess,

Ceramic 11th

Century

The Ayyubides, who reigned from 1751 to 1250, after defeating the Fatimids, left little evidence of their presence: instead of building and decorating monuments, they were more interested in erasing traces of the exuberant Fatimid period, for example the figurative relief work featuring animals and human beings intertwined with verses from the Koran or foliage scrolls.

Ironically it was the fanaticism of the Ayyubides, who restored strict orthodox Sunnism to Egypt, which ensured that many Fatimid works of art can still be admired today: workers were instructed to use the same pieces of wood, marble and ivory, simply turning them around to hide the ornamental details. As a result, modern archaeologists conducting digs have simply turned them around the other away to find the splendour of the original piece fully preserved. Such are the quirks of history.

The Cairo of the Fatimids is the historic part of Cairo as it stands today. Except in Khan El Khallili, here everyone can find everything imaginable, including the last surviving glass-blowers in the city and traditional perfume-makers who, on request, will combine scents to produce a smooth and totally original fragrance, and where people bargain freely, very few tourists are seen.

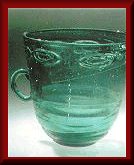

Blue

glass mug, 10th century

Blue

glass mug, 10th century

A simple stroll is an exhausting but exciting adventure. At any and every moment, at any and every point, there are tooting horns, cars backfiring, stands and street sellers calling out to tout their wonderful wares, for example the hat-maker who is the last to make traditional white, black or maroon chechias, the preferred style of King Faruk who last won the throne in 1952; or there is the fascinating book-binder near the mosque of El-Azhar and the attractive house of Harawi, restored by a French mission and offering “notebooks” of every size, bound in semi-shagreen bearing the customer’s name etched in gold.

The visitor may very well feel that he has been transported back to the 19th century, when travellers felt duty bound to keep a travel log of personal observations and impression or even sketches.

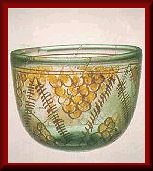

Bowl,

10th - 12th century

Bowl,

10th - 12th century

By the time

the visitor has finished his excursion, filled with colours, fragrances

and striking impressions, it is time to have a break and a snack at the

Café El-Fishawy in the heart of the bazaar, a 19th century bistro

decorated in Ottoman style (reminiscent of scenes on the edge of the Bosporus),

to enjoy the atmosphere here where the citizens of Cairo gather to sip

mint tea and nibble on pistachios while puffing on a famous chicha or narghile

pipe, sending up clouds of aromatic smoke scented with apple or rose.

Ibn

Tulun Mosque

Ibn

Tulun Mosque

Time certainly seems to have stood still, caught in ancient times, or at least to be moving slowly, at the same rate as the Nile which has been flowing just short distance away for thousands of years and was part of the past of the Fatimids.

![]() Tresors

Fatimides du Caire Visit

the Exposition online at Institut du Monde Arabe. A sumptuous collection,

a veritable feast for the eyes! Remember to navigate through all the slides

and the descriptions in French. Even if you don't know French, you'll recognize

the mention of our beloved Imams Al-Muizz and Al-Aziz (please recite Salwaat).

Enjoy!

Tresors

Fatimides du Caire Visit

the Exposition online at Institut du Monde Arabe. A sumptuous collection,

a veritable feast for the eyes! Remember to navigate through all the slides

and the descriptions in French. Even if you don't know French, you'll recognize

the mention of our beloved Imams Al-Muizz and Al-Aziz (please recite Salwaat).

Enjoy!

Rongée

par les intrigues de cour, livrée aux ambitions de ministres et

de vizirs

dominant de leur puissance des califes intronisés dès l’âge

tendre, devant faire face à

un schisme divisant sa propre secte ismaélienne en même temps

qu’à la considérable

pression militaire des Croisés, la dynastie des Fatimides dut subir

en sa capitale des

occupations des armées franque puis syrienne. Elle s’éteignit

en 1171, après un coup

de grâce donné par son dernier vizir, un officier de l’armée

syrienne dont l’Histoire

allait retenir le nom : Saladin. Le vendredi 10 septembre, après

que le dernier calife

fatimide, al-’Âdid, eut été détrôné,

la prière se fit à nouveau au nom du calife

abbasside de Bagdad.

Pour autant, l’art fatimide n’allait pas si facilement s’éteindre.

Émerveillés par sa

splendeur, pèlerins et croisés ne s’étaient pas privés

de rapporter chez eux tous les

objets précieux que pouvaient contenir leurs bagages. Dès

1068, après de violents

troubles et le pillage du trésor des palais, avaient été

vendus sur les étals des

marchands du Caire, à des prix dérisoires, cristaux de roche,

bijoux précieux, étoffes

tissées d’or et de soie, ivoires et manuscrits enluminés.

La célèbre aiguière en cristal

du trésor de Saint Marc, déjà évoquée,

provient ainsi de ce trésor pillé. Souvenirs de

pèlerins, trophées de guerre, cadeaux royaux échangés

avec les souverains étrangers,

sac de Constantinople lors de la quatrième croisade furent aussi

à l’origine de la

présence de l’art fatimide dans les églises et les palais

d’Occident. Les trésors des

églises médiévales, en particulier, reçurent

volontiers les objets d’art fatimides, pour

leurs matières précieuses et leur qualité d’exécution,

et le clergé les « christianisa »

en leur donnant un rôle dans l’apparat des rituels. Au point qu’après

quelques

générations, on avait souvent oublié leur origine.

Caution! - Here is a machine translation of the above (slightly edited):

Harranged by the intrigues of the court, the ambitions of ministers and viziers dominating their power on the caliphs established in tender years, having to face a schism dividing its own Ismailian sect at the same time as with the considerable military pressure of the Crusades, the dynasty of Fatimides had to undergo in its Syrian capital of the occupations of the French armies then. It died out in 1171, after a death-blow given by its last vizier, an officer of the Syrian army whose History was going to retain the name: Saladin. Friday September 10, after the last caliph fatimide, Al-' Âdid, had been dethroned, the prayer was recited in the name of Abassid caliph of Baghdad. For as much, the Fatimid art was not going to so easily die out. Filled with wonder by its splendour, the pilgrims and crossed had not deprived themselves to bring back on their premises all the invaluable objects which could contain their luggage. As of 1068, afterwards of turbid violent ones and the plundering of the treasure of the palates, had been sold on the stalls of the merchants of Cairo, at ridiculous prices, rock crystals, invaluable jewels, woven silk and gold fabrics, ivories and manuscripts enluminés. The famous crystal ewer of the treasure of Saint Marc, already evoked, comes thus from this plundered treasure. Memories of pilgrims, trophies of war, royal gifts exchanged with the foreign sovereigns, bag of Constantinople at the time of the fourth crusade were also at the origin of the presence of the Fatimid art in the churches and the palaces of the Occident. The treasures of the medieval churches, in particular, accepted readily the Fatimid objets d'art, for their precious substances and their quality of execution, and the clergy christianized them in their giving a ritual role in the pageantry. So much so that after some generations, one had often forgotten their origin.

Other Related Material on the Ismaili Web