“Have you not considered how God sets forth the parable of a good word (being) like a good tree, whose root is firm and whose branches are in heaven,

Giving its fruit at every season by permission of its Lord? Allah coineth the similitudes for mankind in order that they may reflect.”

Quran: Surah Ibrahim: 14:24-25

14:24 الم تر كيف ضرب الله مثلا كلمة طيبة كشجرة طيبة اصلها ثابت وفرعها فى السماء

14:24 Alam tara kayfa daraba Allahumathalan kalimatan tayyibatan kashajaratin tayyibatinasluha thabitun wafarAAuha fee alssama/-i

14:25 توتى اكلها كل حين باذن ربها ويضرب الله الامثال للناس لعلهم يتذكرون

14:25 Tu/tee okulaha kulla heeninbi-ithni rabbiha wayadribu Allahual-amthala lilnnasi laAAallahum yatathakkaroona

A Good Word is Like a Good Tree

by Annemarie Schimmel

March 1996

Honourable assembly, Your Honour Mr. President. I am very grateful for the guiding speech by which you honoured me and in which you emphasised so strongly the importance of tolerance and of understanding foreign civilisations, which are indispensable to our foreign politics. When I learnt to my great surprise and joy that I had been awarded the Peace Prize, nobody would have imagined that during the following months a campaign would unfold – a campaign of such force that it seemed to destroy my life’s work, which was and is devoted to a better understanding between East and West.2 This hurt me to the very core of my heart and mind, and I hope that those who attacked me without even knowing me in person or having read my works will never have to undergo a torture like that.

I learnt one thing: the methods and ways of scholarship and poetry are one thing, those of journalism and politics something else. Both sides however agree on one point: that is the central role of the word, the free word, in our lives.

I think during the last months I have stated often enough that I loath the disastrous fatwa against Salman Rushdie and I will help in my own way to defend the freedom of speech, of the word. In the 1950s my Pakistani poet friend Fez wrote from prison;

“Speak! for your lips are still free,

speak! for your tongue is still yours,

speak! your straight body is still yours,

speak! for your life is still yours,

See, how in the Blacksmith’s forge

the flames are sharp, the iron is red,

The locks’ mouth begin to open,

every rind in the chain becomes wide!

Speak a little, time is plenty

before body’s and tongue’s death.

Speak, truth is still alive,

speak out, whatever is to be said.”

And this leads me to the very subject of my address. Sometimes I thought: if Friedrich Ruckert (1788-1866) were still alive he would certainly deserve the Peace Prize, as his motto was: “Weltpoesie (global poetry) alone is Weltversohnung (leading to the reconciliation of worlds)”. During his lifetime, he produced thousands of masterly poetical translations from dozens of languages and knew that poetry, “the mother tongue of the human race”, connects people as it is part of all civilisations.

And this leads me to the very subject of my address. Sometimes I thought: if Friedrich Ruckert (1788-1866) were still alive he would certainly deserve the Peace Prize, as his motto was: “Weltpoesie (global poetry) alone is Weltversohnung (leading to the reconciliation of worlds)”. During his lifetime, he produced thousands of masterly poetical translations from dozens of languages and knew that poetry, “the mother tongue of the human race”, connects people as it is part of all civilisations.

But in the period when Ruckert spoke of poetry as the medium of global reconciliation, and that means, of peace, people had a different relationship with the non-Western world from what we have now. Amazed and shocked, the West had observed in the 8th and 9th centuries the Muslim conquest of the Mediterranean, but thanks to the Arabs who ruled Andalusia for centuries, it has also inherited the foundations of modern science; medical works by Rhazes and Avicenna were considered standard works in Europe to the beginning of modern times; the writings of Averroes played a role in theological discussions and prepared the way towards the Enlightenment. The translations of Toledo, where Jews, Christians and Muslims lived peacefully together, made Arab learning the poetry of the West. The Catelan scholar Ramon Lull, again, taught the mutual respect of religions which, in his opinion, should end not only in discussion but lead to a common enterprise – that is to foster peace.

After the siege of Vienna by the Turks in 1529, bloody dramas about the Turks were part and parcel of a widespread anti-Turkish, and that meant anti-Islamic literature, but at the same time, Europe came to know another aspect of the East thanks to objective reports by travellers and merchants. The first French translation of the Arabian Nights at the beginning of the 10th century showed the West an oriental world of fairies, jinnies and sensual attractions which inspired generations of poets, painters, and musicians; at the same time Arabic and Islamic studies as well as Indology gained an independent status among the sciences thanks to the Enlightenment. Scholarly studies and translations triggered off a current of orientalising poetry, which was headed by Goethe, whose West-Oestrlicher Divan with its “notes and dissertations” is an unsurpassed analysis of Islamic culture.

But when Ruckert published his first poems inspired by Persian poetry in 1820 (one year after Goethe’s Divan) people listened to the tales “when far away in Turkey people fight each other” (as Goethe says in Faust).

As for us, we are not only informed day after day of news events but rather are entangled by the mass media to watch pictures of the Muslim world, to which we owe so much. This culture appears strange and alien to most Europeans, and is constantly blamed because it seems to have no reformation, no Enlightenment, and is therefore considered “incapable of changing” as Jacob Burckhardt claimed a century ago with a deadly aversion. But do not most people know that the Islamic world between Indonesia and West Africa presents us with most diverse culture expressions, although it has the common basis in the firm belief in the One and Unique God and the acceptance of Muhammad as the last Prophet? To look at the Islamic world as something monolithic is as if we would overlook in the West the difference between Greek orthodox Christianity and North American Freechurches. But in times where we are constantly flooded with condensed, brief information, it seems next to impossible to differentiate, and to recognise the softer shades and positive aspects of Islam as it is lived.

“Man is the enemy of what he does not know” says the Greek as well as the Arabic proverb. Maulana Rumi, the great mystical poet of the 13th century, tells in his Persian prose work that a little boy complained to his mother of a black figure that appears time and again to frighten him; finally the mother advises him to address the terrible apparition, as one can recognise someone’s character by his answer. For the word, as Persian poets like to repeat, discloses the speaker’s character by its “smell”, just as an almond cake stuffed with garlic discloses its true character although it may outwardly look quite appetising.

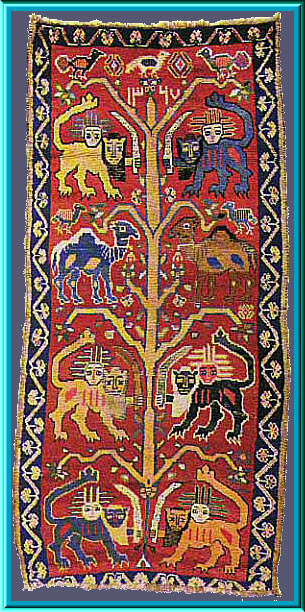

“A good word is like a good tree.” Thus says the Quran, and in most religions the word is regarded as the creative power; it is the carrier of revelation: God’s word incarnate in Christianity, or His word inlibrate in Islam. The word is a good entrusted to man, which he should preserve and which he must not weaken, falsify, or kill by talking too much. For it has a power of its own which we cannot gauge, it is this power of the word upon which rests the extraordinary responsibility of the poet and even more of the translator who by a single wrong nuance can cause dangerous misunderstandings.

The ancient Arabs believed that the poets’ words were like arrows, and even in the Gulf War the Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussain used poets to propagate his will to victory. The power of poetry is much greater in the Islamic world than with us; we are touched by music, the Muslim mostly by the sound of language.

I have discovered Istanbul corner by corner through the verses which Turkish poets had sung for five centuries about this wonderful city; I have learnt to love the culture of Pakistan through the songs that resound in all of its provinces, and when one of my Harvard students had the misfortune to be among the American hostages in Tehran, he experienced a great change in his jailers’ attitude when he recited Persian poetry; here, suddenly, a common idiom emerged and helped to bridge deep ideological differences.

I agree with Herder’s words: “It is from poetry that we gain a deeper knowledge of times and nations than we do from the deceptive miserable way of political and martial history.”

The long dirges which Urdu poets in 19th century India wrote in memory of the martyrdom of Hussain, the prophet’s grandson, served at the same time to criticise the British colonial power in coded words. We have to decode them to understand their explosive political message.

For centuries poets have complained about exile and jail. It is sufficient to mention the contemporary Iraqi poet al-Dayati:

“I dreamt, and separation,

oh beloved, was pain

for I am homeless

I die in a foreign town

die alone, oh my beloved,

without a fatherland.”

Hermann Hesse, whose Morgenlandfahrt is well-known to all of us, said in his Peace Prize speech in 1955: “It is not the poets’ affair to accommodate to any actual reality and to glorify it, but rather to show beyond it the possibility of beauty, of love, and of peace.” Did not the Lebanese poet Adonis intend the same thing when he wrote during the horrors of the Lebanese civil war:

“Take a rose, spread it out as a pillow

after a little while

weakness will devour you

in murky dirt

heavy bombs will make you

their victim

after a little while

Take a rose and call it songs

and sing it for the world”

The later poetry of Islamic peoples is largely influenced by mysticism, but one should not, as is usual, equate mysticism with obscurantism, with fleeing from reality or as something that has no meaning for post-Enlightenment people. Many of the great mystics were rebels against what they regarded as injustice, against corrupt states, against hairsplitting jurists who, as the great thinker Al-Ghazali in the 11th century wrote in his autobiography, “knew the tiniest details of the divorce laws but knew nothing of God’s living presence”. Such an attitude of mystics is found in all religious traditions; in Christianity, male and female saints actively tried to change the fate of their countries, and the same is true for the Chassidim in Eastern Europe as we understand from Martin Buber’s books. Because they emphasised spiritual values, these people often came to criticise the society intensely and became fighters for social justice.

The history of Islam contains numerous names of such mystics, whose lives were devoted to the realisation of their love of God and mankind. The greatest among them is al-Hallaj, who was executed in Baghdad in 922, in part because of his daring religious claims but in part because of his political activities. He remains a symbol for the Muslims to this day, hated by the traditional orthodox, admired by those who regard him not only as the representative of pure love of God but also as a fighter against the establishment. His parable of the moth that casts itself in the flame to gain new life through dying inspired Goethe’s famous poem “Selige Sehnsucht”. The apotheosis of this “martyr of Divine love” whose name is conjured up by progressive writers in all Islamic countries is a scene in Iqbal’s Persian epic, Javidname, where Hallaj warns the modern poets:

“You do exactly what I once did – beware!

You bring resurrection to the dead – beware!”

That is, resurrection from a fossilised world of legalism, and this is by denying human responsibility but as a fulfilment of man’s real role in the world. Does not the Quran state that God has honoured humans by entrusting to them a precious good (Sura 33:72)? Iqbal, the spiritual father of Pakistan, is perhaps the best example of a modern interpretation of Islam. His poetry was on everyone’s lips in India in the 1930s, for the largely illiterate masses could be reached only by the poetical word which can be memorised easily. Iqbal (whose works, incidentally are banned in Saudia Arabia) had under the influence of Goethe and Rumi, tried to postulate a dynamic Islam; he was aware that the human being is called on to improve God’s earth in cooperation with the Creator, and that one should exhaust the never-ending possibilities of interpreting the Quran in order to survive changing circumstances. But he also taught that one never should rely exclusively upon intellect, as much as modern technology and progress can be admired and man is called on to participate in it. In a central poem of his, “Message of the East”, his answer to Goethe’s “Divan”, he writes that science and love, that is critical analysis and loving synthesis, must work together to create positive values for the future.

This brings us to a point which appears increasingly important to me – this is the problem of lovingly understanding foreign civilisations. Unfortunately the word “understanding” seems to be equated today with an uncritical acceptance and general forgiveness. Yet, true understanding grows from a knowledge of historical facts and many people lack such a knowledge. Spiritual and political situations however develop out of historical facts which one has to know first before correctly judging a situation.

St. Augustine said “one understands something only as far as one loves it” and our mediaeval theologians knew that “love is the intellect of the eye.” One can of course claim that such a love makes the lover blind, but I believe that such a deep love also opens one’s eyes, for we see all beloved beings’ sins and mistakes with much deeper grief then those of an unknown person. We spent our lives in studying the world of Islam in its manifold facets and tried to show its positive aspects to a public that has barely an idea of this complex world. Therefore for us it is a much more terrible shock to follow the developments that appeared in some parts of the Islamic world during the last decades.

In a civilisation whose traditional greeting is Salam “Peace” (like the Hebrew Shalom) we observe at the moment a horrifying narrowing and stiffening of dogmatic and legalistic positions. At the beginning we believed that this could be explained as an attempt to shut the floodgates against the increasing influence of the West, in order to be such that the believers follow the straight path shown by the Prophet Muhammad. Now, however it looks different: in large areas we are confronted with sheer power politics, with ideologies which utilise Islam more or less as a catchword, and have very little in common with its religious foundations.

At least I have not discovered in the Quran or in the Traditions anything that orders or allows terrorism or the taking of hostages. On the contrary, the Golden Rule is valid everywhere in the world of Islam. No thinking individual can appreciate acts of terror wherever they appear and in whichever ideology they are rooted, and nobody would be happier than we, whatever our special field of research may be, when death sentences or imprisonment of persons of deviant opinions or critical thinkers would no longer be pronounced. Many of the radical fundamentalists seem to forget that the Quran says la ikrah fid-din “no compulsion in religion” and that the Prophet warned against declaring anyone a kafir, an infidel. The fundamentalists try to recruit followers among the unemployed, rootless youth whom they supply with a few simple formulas to manipulate them easily. But such a politically misused Islam is something completely different from lived Islam; it is, as Tahe Ben Jalloun writes, a caricature of true Islam, “for it stands for a political doctrine which was nonexistent until now in the Arab-Islamic world”.

But the image of the West in the media of the different Islamic countries is also often distorted, and we need to enlighten both sides. Strangely enough even liberal Muslim intellectuals are but little aware of their own history and the works that Muslims in other parts of the world have created; they are most grateful when they are gently led to recognise the great traditions of their own civilisations which nowadays often seem to be forgotten under a crust of centuries-old developments and yet could help them find their own way into a modern future that is genuinely their own. Gently, I said, and not by lifting one’s index finger like a teacher for that can result immediately in a negative reaction to suspected “cultural colonialism”.

I speak from experience after giving innumerable lectures during the last 40 years in different oriental countries. During those years that I, a young non-Muslim woman, was occupying the chair of History of Religions in the new faculty of Islamic theology in Ankara (at a time when there were barely any chairs for women in German universities) I had also to teach `Church History and Dogmatics’. And that was very important. For we usually forget the great role Jesus, the “Spirit of God” and his mother play in the Quran and Muslim piety. Once in a while we should remember a sentence which Novalis in his novel “Heinrich von Ofterdingen” (published 1801) put in the mouth of the imprisoned Saracen woman in Jerusalem: “Full of respect, our princes honoured the tomb of your saint whom we too regard as a divine Prophet. How beautiful would it have been if his sacred tomb had become the cradle of a happy understanding and the reason for eternal beneficial alliances …”

Judaism, Christianity, and Islam knew the ideal of eschatological peace where lion and lamb lie together in the time of the just ruler. But peace is nothing static. The UNESCO Declaration about “The role of religion in the promotion of a culture of peace” (Dec. 1994) says: “Peace is a journey, a never ending process.” There is nothing that is not kept alive by the principles of change and polarity; a heart that no longer beats is dead. Peace too is a process of living growth which begins in each of us. The Muslim mystics considered the constant struggle with their lower qualities the real jihad: “the greater war in the way of God” and when their souls had finally reached peace they were capable of working for peace in the world.

One may think that the picture of Islam which I offer is too idealistic, far away from hard political realities, but as a historian of religion I learned that one has to compare ideal with ideal. The Swedish Lutheran Bishop Tor Andrae (d.1948) a leading Islamologist, wrote in his biography of Muhammad: “A religious faith has the same right as every other spiritual movement to be judged according to what it really intends and not according to how human weakness and contemptibleness have stained this ideal”.

My picture of Islam has emerged not only from a decades-long interest in Islamic literature and art, but even more from the friendship with Muslims all over the world and from all levels of the population, who accepted me into their families and acquainted me with the poetry of their languages. I owe them an enormous gratitude, a small part of which I want to acknowledge today. People like Mevlude Genc, the Turkish woman in Solingen who forgave those who caused the loss of many of her family members, are representatives of that tolerant Islam which I have known for so many years. I am so grateful to my parents who educated me in an atmosphere of religious freedom, permeated by poetry, as well as to my teachers, colleagues and students each of whom has expanded my horizons in his or her special way.

I am most grateful to the Borsenverein whose election committee had the courage to elect me into the illustrious circle of the recipients of the Peace Prize, although Ibn Khaldun, the great North African philosopher of history in the 14th century says in the headline of one of his chapters that “the scholar is one who among all people is least acquainted with the ways of day-to-day politics.”

The scholar’s duty is to explain cultures to himself and to others. Martin Buber pointed out in this place in 1953 that the acceptance of the other is the basis of dialogue. That is also true of the relations between the West and the Islamic world, as much as Islam appears to be the enemy after the end of the East-West conflict. Yet, like Buber, I still believe in true dialogue, which, as he says, consists in the acceptance of the other as he is, for only thus differences can be overcome – though not taken out completely – in a human way.

This Peace Prize is an honour – which I had never dared dream of, and it will be an incentive to continue and increase my efforts for a better understanding between the Occident and the Orient as long as my strength will last. The words which the President of the Federal Republic of Germany has addressed to me will strengthen me on this path. But first and last I owe my thanks to Him about whom Goethe says in his “West-Ostlicher Divan”:

“The East belongs to God

The West belongs to God

northern and southern lands

rest in the peace of His hands,

He, the sole just ruler,

intends the right things for every one,

Among His hundred names

– be this one glorified and praised

Amen.”

Annemarie Schimmel

March 1996

Endnotes

- 1. The above speech was delivered to an assembly of writers, publishers and public officials, including the President of the Federal Republic of Germany, Roman Herzog, on the occasion of the bestowal of the German Book Trade’s annual Peace Prize to Annemarie Schimmel. The speech was translated from German and published in the London-based weekly, Q-News. JUST has reproduced the speech with the kind permission of Q-News.

2. When the award of the Peace Prize to Schimmel was first announced in April 1995, two hundred German and European intellectuals protested on the grounds that she was a supporter of so-called Islamic fundamentalism. A number of other groups and individuals in Germany and elsewhere, however, came to her defence and rejected the malicious allegations against Schimmel. JUST was one of those organisations that submitted a petition to the German government on her behalf.

Annemarie Schimmel is one of the most outstanding German scholars on Islam. She is the author of numerous books and essays on sufism, spirituality and Islamic culture. Annemarie Schimmel, SI, HI, (April 7, 1922 in Erfurt, Germany – January 26, 2003 in Bonn, Germany) was a well known and very influential German Orientalist and scholar, who wrote extensively on Islam and Sufism. She was a professor at Harvard University from 1967 to 1992. She was briefly married in 1955 in Ankara to a Turk, adopting Cemile as her Muslim name. Although she had no immediate living family, she is survived by a well-loved son of a cousin and his family.

Related Links

![]() Islam: The Next American Religion?

Islam: The Next American Religion?

![]() Ismaili da’wa Outside the Fatimid dawla

Ismaili da’wa Outside the Fatimid dawla

![]() Introduction to Ismailism by Dr. Sheikh Khodr Hamawi

Introduction to Ismailism by Dr. Sheikh Khodr Hamawi

![]() The Importance of Studying Ismailism by Professor Ivanow

The Importance of Studying Ismailism by Professor Ivanow

![]() The Importance of Spiritual Literacy

The Importance of Spiritual Literacy

![]() The Religion of My Ancestors by Aga Khan III – Mowlana Sultan Mahomed Shah

The Religion of My Ancestors by Aga Khan III – Mowlana Sultan Mahomed Shah

Pingback: Gregory Smith

I have read and listened to A.Schimmell when she was in Toronto in the late 1980’s

Came upon this speech at the Right time!!! thank you for an excellent site. May Allah guide you in your work. Ameen.

Pingback: Islamic Scholar John Esposito Talks about Faith, Pluralism, and the Challenges Facing Islam Today --- by Katherine Schimmel Baki

Pingback: Islamic Scholar John Esposito Talks about Faith, Pluralism, and the Challenges Facing Islam Today | Ismaili Web Amaana

Easy to understand, I like your work!

We are a gaggle of volunteers and starting a brand new scheme in our community. Your web site provided us with valuable info to work on. You’ve done an impressive activity and our whole neighborhood shall be thankful to you.

Great article, exactly what I needed.

Interesting site.

Wow! This is the most beautiful website. Basically Excellent. I am also an expert in website design therefore I can understand your hard work.

Pingback: A Good Word is Like a Good Tree – Annemarie Schimmel | Ismaili Web Amaana | Ismailimail

Hi there very nice blog!! Beautiful .. Amazing .. I will bookmark your web site and take the feeds additionally I am happy to search out numerous useful information here in the put up, thank you for sharing. . .

That is really fascinating, You are a very professional blogger. I’ve joined your rss feed and stay up for in search of more of your great post. Additionally, I have shared your site in my social networks