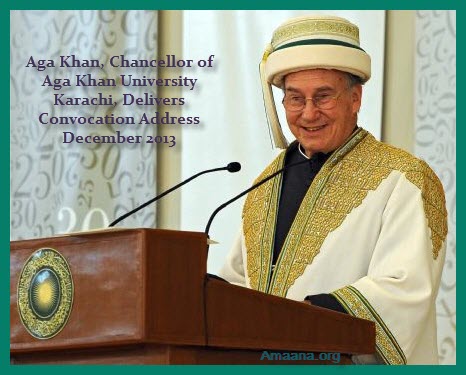

Karachi, 19 December 2013

Karachi, 19 December 2013

His Excellency, Dr Ishrat Ul Ebad Khan, the Governor of Sindh;

His Excellency, Qaim Ali Shah, the Chief Minister of Sindh;

Acting Chairman, Dr Robert Buchanan and Members of the Board of Trustees;

President Firoz Rasul;

Provost, Deans, Faculty and Staff of the University;

Members of the Diplomatic Corps;

Members of the National and Provincial Assemblies;

Parents, supporters and distinguished guests;

and Graduands:

As Salaam–o Alaikum

It is truly a great pleasure for me to celebrate this milestone moment with all of you today. It is a significant time for our University and for this country.

As Chancellor, I am delighted, first of all, to extend my warmest congratulations to our graduands and to your families. Bravo! We wish you enormous success in your future careers, knowing that your success will be a mark of our success.

I earnestly hope, however, that you will not think of this convocation as a farewell ceremony. We look forward, rather, to your continuing participation in University life. Perhaps, like many graduates, you may become members of our faculty or senior staff as time goes by, or participants in continuing education programmes or alumni groups, or sponsors of special programmes, including scholarships for students of promising ability but scarce material resources.

As graduands you will be joining an illustrious family of earlier graduates. Many of our alumni are here today and I am pleased to extend to them, as well, my heartfelt greetings. When you first came as students to AKU, you did not know us and we did not know you, and yet we came to have great faith in one another. And you have fully justified that faith, using your education for good and great purposes.

The academic heart of the University, of course, is our Faculty, and I know I speak for all of you in paying special tribute to them today. The exemplary devotion of our Faculty, both to their students and to their disciplines, is the bedrock on which our University is built.

Another constituency that I am proud to salute today are the donors who have shared the goals of this young institution, and have assisted it so much in their accomplishment. University success stories down through history, in the Islamic world and the West, have depended, inevitably, on a variety of external resources, and we are indebted to those who have provided such resources for AKU. Those resources, let me add, include not only material gifts, but also the great gifts of time and knowledge that so many contribute to our progress.

The University’s Management, of course, also deserves special thanks, as it works daily to coordinate our energies and sustain our functioning, not only here in Karachi, but, uniquely, on multiple international campuses.

Finally, let me mention the immense good fortune we have enjoyed through the work of our distinguished Trustees. From the start, they have been leaders of exceptional competence and dedication, bringing to us the fruit of their distinctive personal experiences, as well their wise global perspectives. Each of our trustees over the past thirty years has left a lasting imprint on the University.

All of you from these and other constituencies have provided the energies and the talents, the dreams and the discipline, that drive this institution forward. And, as we go forward, we will take continuing strength from one another.

At the same time, on a day like this, we can also take renewed strength from our past, and from a great legacy of Islamic accomplishment in pursuing educational excellence.

That legacy has long been an inspiration to me, even from the time when I succeeded my grandfather as Imam in 1957, when I was a University student at Harvard. That’s some time ago!

My grandfather, Sir Sultan Mahomed Shah Aga Khan, was deeply aware of Islam’s rich intellectual heritage. Of equal significance, he was also convinced of the enormous importance of higher education for the future of the Ummah around the world.

He had engaged personally in developing educational opportunities for Muslims in pre-partition India – and was largely responsible for creating Aligarh University. He saw that effort as fulfilling a tradition going back one thousand years, to the role of his predecessors, the Fatimids, in founding the Azhar University and the Dar ul-Ilm in Cairo, known through the ages as the “House of Knowledge.”

He knew as well about other great Muslim institutions of scholarship and culture which flourished over many centuries, serving the whole of the Ummah and much of the known world, engaging the most advanced thinking from many cultures, ethnic groups and faith communities.

It was true of the Fatimids 1,000 years ago and of the Abbasids in Baghdad even earlier. It was true of the Mughal Emperor Akbar in the 16th century as well as the Ottoman Sultans, including Mehmed the Conqueror and Sulayman the Magnificent. And there were many others; the Safavid ruler Shah Abbasin Sifahan in Iran, and the great Timurid Sultan, Ulugh Beg, who built the world’s greatest observatory in Samarkand. You have just heard about some of the great intellects who flourished under these auspices.

Whenever and wherever it may have been, in the Middle East, or South, or Central Asia, or Northern Africa, the most brilliant periods in Islamic history were marked by an expansive quest for intellectual excellence.

It was this tradition that I inherited from my grandfather – and it was not a static tradition, but one that was built around the power of new knowledge and the great adventure of learning how to go on learning.

Now, of course, we also know that institutions of higher learning are very costly. We know, too, that as the industrialised world grew economically, and as the Ottoman empire faded, prominent centres of knowledge emerged most rapidly in the West. Meanwhile, universities in the Muslim world, with some exceptions, generally tended to tread water.

It was this situation that confronted us as we began to plan AKU. We had high hopes, but, to be candid, we also felt some trepidation. Was higher education still a central pillar around which to build the quest for human development? Were the costs justifiable when compared to other priorities? If we went forward, could we find appropriate allies, including a distinguished faculty? Would graduates emigrate to developed societies – rather than staying to serve their home communities?

The fundamental question, in sum, was whether a new university in the developing world, in this day and age, could achieve sufficient levels of excellence – as measured by global standards – to bring genuine value to those we were committed to serve.

We felt that we answered these questions successfully, but preliminarily if not conclusively, when we began this great adventure. And I think we can fairly say that the University has performed well when measured against our original goals.

Simply in quantitative terms, AKU expanded over the years into eight different countries, opening unique opportunities for combined study in Asia and in Africa. We created two degree or diploma programmes in the 1980’s, two more in the 1990’s, and another 21 programmes since the year 2000, reflecting expanding arcs of knowledge. These programmes have now graduated over ten thousand students.

But this growth in numbers would mean little, in fact it would have been impossible, without an uncompromising commitment to quality.

Happily, as we heard earlier, the quality of AKU’s performance has been widely affirmed, by the Joint Commission, by the World Health Organization, and by governmental and educational bodies in Pakistan and elsewhere. We are proud, too, that our graduates are consistently judged to be among the best when they take licensing exams or apply to other leading institutions, or assume growing career responsibilities.

A key ingredient in this story has been our open-access philosophy, enabling us to enroll students, on merit, from a vast array of backgrounds; some 70 percent of current students receive some form of financial support. And another critical standard, of course, has been AKU’s resolute commitment to social relevance, to addressing real problems and improving the quality of daily life.

For all of these reasons we can say that our recent past, like our distant past, has been one of proud accomplishment. And it is upon these accomplishments that we now seek to build the University’s future.

As we do so, we are sharply aware that the pace of change is accelerating, that our global neighbourhood is shrinking, and that the best prediction about the future is that it is highly unpredictable.

In such a world, creativity and flexibility will be essential to our success.

Our founding blueprint for AKU embraced this understanding and an evolving development process. It called for concentrating, in AKU’s first years, in the fields of healthcare and education, responding to the most pressing national and regional needs. But it also anticipated the University’s expansion into new geographic areas and into new fields of knowledge. In fulfilling that vision AKU has become a multi-campus university, indeed a multi-continental one, launching new programmes in Kenya, in Tanzania and Uganda, countries with significant Muslim populations.

In addition, the Trustees have also embraced a second great challenge – the challenge of becoming a distinguished liberal arts university.

We are planning now to build new undergraduate Faculties of Arts and Sciences, one in Karachi and one in Arusha in Tanzania. We plan to achieve this goal progressively as circumstances and resources allow. Yes, it will be a time-consuming exercise, but our planning has been advancing very quickly indeed.

Again, developing a liberal arts capacity will not only fulfill AKU’s founding vision, but it will also follow in the tradition of the great Islamic Universities of past centuries, and their effort to expand, and to integrate a wide array of knowledge. At that time, of course comprehending the full expanse of knowledge was seen as an achievable goal; today, the explosion of knowledge seems overwhelming. But the knowledge explosion is precisely what makes a liberal arts platform even more valuable. The liberal arts, I believe, can provide an ideal context for fostering inter-disciplinary learning, nurturing critical thinking, inculcating ethical values, and helping students to learn how to go on learning about our ever-evolving universe.

A liberal arts orientation will also help prepare students for leadership in a world where the forces of civil society will play an increasingly pivotal role.

By civil society I mean a complex array of organisations that operate on a private, voluntary basis, but are driven by public motivations. They include institutions dedicated to culture, health, education, and the environment; they embrace commercial, labour, professional, scientific and ethnic associations, as well as institutions of religion and the media. We have seen the growing role of civil society in many places – in the industrialised West, in the developing societies of Africa, and through the Islamic world as well, from Egypt and Tunisia to Iran and Bangladesh.

In places where government has been ineffective, or in post-conflict situations, civil society has demonstrated its potential value for maintaining, and even enhancing, the quality of human life. But civil society requires leaders who possess not only well-honed specialised skills, but also a welcoming attitude to a broad array of disciplines and outlooks.

This is why we believe that an investment in liberal arts education is also an investment in strengthening civil society. And this is also true of another, complementary investment we will be making at AKU – the creation of seven new graduate professional schools.

These schools will work in fields of particular relevance to developing societies. Through their degree programmes, through their research and through continuing education, they will also develop able and ethical leaders who can strengthen the role of civil society among the people we seek to serve.

To guide our planning for these schools, we have set up special Thinking Groups in each of these fields, drawing on global expertise and best-practice experience. Our planning has been deeply enriched by their remarkable analyses.

These new graduate schools are exciting.

Our new School of Media and Communications is already building capacity in Nairobi to help lift the quality of media industries in the developing world, engaging with new technologies and with appropriately educated proprietors, managers, and practitioners.

The School of Leadership and Management will develop the capacity of its students to guide business organisations, but also social enterprises and civil society institutions amid the complex challenges that face developing countries.

The Leisure and Tourism programme, meanwhile, will focus on the broad tourism value- chain, from public policy to infrastructure to cultural assets, while helping to fill an important research gap in this critical field.

The School of Architecture and Human Settlements, on the other hand, will build enhanced design professionalism, emphasising functionality and cultural sensitivity, in urban and rural environments, recognising the profound impact of the built environment on the quality of life.

The School of Government, Public Policy and Civil Society will prepare and empower professionals to formulate and implement public policies in developing societies, while our new School of Law will focus on subjects such as constitutional devolution, international law, dispute resolution, intellectual and real property, and the management of capital markets.

Finally, a programme in Economic Growth and Development will respond to the particular needs of developing economies, including fields such as agriculture and horticulture, tourism and leisure, the extractive industries, and digital arts and services.

We intend that each of these schools should work closely with our existing faculties, in nursing, medicine and education, while coordinating effectively with our new Faculties of Arts and Sciences, and indeed with one another, sharing perspectives and inter-disciplinary opportunities.

Meanwhile, we also expect to continue our geographic expansion and to build new partnerships with universities in the West, in the East and the Global South.

This is an outline then of what AKU may look like thirty years from now. These will seem to be ambitious goals – some may say they are too ambitious. But I disagree. Our goals were ambitious, after all, back in 1983. And yet, if we could have glimpsed into the future then – if we could have forecast what this day would look like – I think we would have been very happy with the way the story has unfolded.

And so it is that we see ourselves today in the context of a rich historical tradition, and a recent past filled with genuine achievement. For that, I want to express again, to all of you, the deep sense of joy and gratitude that I feel as I join you for this celebration, and as we look together to our challenging, promising future.

Thank you.

- Speech by His Highness the Aga Khan Upon Receiving the Gold Medal by the RAIC, Canada

- Aga Khan Receives Doctor of Sacred Letters Degree from Trinity College University of Toronto

- Aga Khan Speeches, Interviews and Writing – Nanowisdoms Part 2 – LATEST!

- Aga Khan Speeches, Interviews and Writing – Nanowisdoms Part 1 – PAST SPEECHES

- Collection of Speeches by His Highness the Aga Khan at the Ismaili Web

- Collection of Interviews of His Highness the Aga Khan at the Ismaili Web

- Mowlana Hazar Imam’s Speeches on Islamic Architecture

- Review Quotes:

- Islamic Architecture Speeches by Mowlana Hazar Imam

- His Highness the Aga Khan’s Address at the 25th Anniversary Graduation Ceremony of the Institute of Ismaili Studies October 20, 2003

- His Highness the Aga Khan’s Speech at the Institute of Ismaili Studies 25th Anniversary Colloquium October 19, 2003