August 6, 2001 Safe Harbour

CLIVE SHIRLEY in Ashgabat

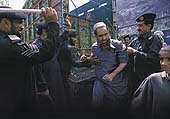

Photo: Clive Shirley THE FIRST OF 94 ISMAILI HAZARAS, CARRYING NOTHING BUT hope, stepped off a flight in Montreal on July 18 from Ashgabat, Turkmenistan, a Central Asian state neighbouring war-torn Afghanistan. The Hazaras, Shiite Muslims, were once the third-largest ethnic group in Afghanistan, numbering close to five million in the country of 23 million. But their fortunes changed in the chaos that began with the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 and has continued in the wake of the 1996 victory by the Taliban in the country's civil war. The Taliban -- "seekers of the truth" -- have established an extreme fundamentalist Sunni Muslim regime, murdering hundreds of Hazaras and driving thousands from the country. A lucky few are coming to Canada. As they struggled to learn French in preparation for their new life in Quebec, they told Maclean's their stories:

THE SOUND OF DOZENS OF voices, male and female, young and old, belting out a chorus of Alouette, emanates from the basement of an office building in Ashgabat. "Je te plumerai la tete, je te plumerai la tete," they shout in barely recognizable French along with Zoulphia Groutou, their instructor with the Geneva-based International Federation of Red Crescent Societies. Her students, aged five to 75, attend a two-hour lesson once a week. And when Maclean's visited the classroom -- the men and young people at the front, women and elderly at the back -- all stood to greet their visitor with a hearty "Bonjour." Male heads of families are under the most pressure to learn, but it's the teenagers who excel, especially the young women who are anxious to read French so they can decipher the colourful pages of the fashion magazines donated to the class by the French Embassy. Their instructor's goal: provide them with a linguistic survival kit for their new home. "Most will be able to buy a bus or a train ticket," Groutou says, "or ask for directions."

Photo: Clive Shirley Many were tortured; some died. Now, after their long and dangerous journey, the Ismaili Hazaras are learning French in preparation for their new lives in the province of Quebec The Ismaili Hazara lived in Afghanistan for centuries, operating small shops, trading commodities such as wheat and sugar. Their lives changed forever when the Soviet Union invaded the mountainous country in 1979 to support a Communist regime in Kabul and control the spread of Islamic fundamentalism along its border. For 10 years, Soviet troops supported by jet fighters and helicopter gunships battled the Afghani mujahedeen -- holy warriors. The Soviets expected an easy victory, but the guerrillas retreated into the mountains and, with U.S.-supplied weapons, including portable anti-aircraft rockets, fought the invaders to a standstill. Unable to subdue the mujahedeen, and with casualties mounting, the Soviets finally withdrew in February, 1989.

But the heavily armed mujahedeen, an uneasy alliance of guerrilla groups, quickly broke into factions and fought a bitter civil war. The fighting finally reached Kabul, the capital, in 1992 and all but destroyed the city, forcing more than one million refugees who were not part of the Sunni majority to flee. Many Hazaras joined the lines of trucks and carts heading northwest towards the city of Mazar-I Sharif, an area of the country the Sunnis did not control.

Hussain Ali Haidary, his wife and son, Fraidon, were among those to escape. Sitting on cushions in a cramped Soviet-era apartment in Ashgabat, Haidary tells how they first made their way to Mazar-I Sharif. There, over the next six years, they survived by selling gasoline, a valuable commodity in the shattered country. But in August, 1998, black-turbanned soldiers of the Taliban, which emerged victorious in the civil war, entered the city, where the remnants of many opposing factions had fled. Determined to erase all opposition, they turned their weapons on the largely defenceless population, killing at least 5,000 people.

The Haidarys eluded death again, this time fleeing southwest to the safety of the mountains, along with thousands of others and as much food as they could carry. The Taliban pursued them, attacking with rockets and killing hundreds before the refugees finally reached mountains into which the motorized Taliban army could not advance. Six weeks later, the Taliban leadership announced an amnesty. But it was laced with a threat: those who remained in the mountains would be hunted down and killed. The Haidarys decided to return to Mazar-I Sharif, but instead of being granted amnesty, Fraidon, by then 21, and his father, 65, were imprisoned.

For the next six months, they were repeatedly tortured. The weapon of choice: a horsewhip wielded by religious police from the ministry for the enforcement of virtue and suppression of vice. As his father tells their story, Fraidon sits uncomfortably, as though trying to will those memories away. But the Haidarys were lucky: during their imprisonment, other men were removed from their cells and loaded into trucks -- never to be seen again.

Fraidon believes he and his father were spared because they were healthy. Eventually, they were used as slave labour to build a mosque. By that time, their family had located them and made an unsuccessful attempt to buy their freedom for $1,800 -- in a country where the average monthly wage is $45. An official pocketed the blood money, but a second attempt and a further $900 finally secured their release. They made their escape by truck to neighbouring Turkmenistan.

Photo: Clive Shirley Awaz Ali Haidary and grandson Shohab seek security in Canada Haidary's nephew, Abdulsami Hussainyar, was returning from the mountains two days after his uncle when he was arrested along with 15 other men. They were taken to the basement of a traditional round mud house in Mazar-I Sharif, forced to lie face down with their hands and legs tied behind their backs and beaten savagely with the dreaded "Enforcement of Virtue" whip.

Hussainyar's son, Farid, then 14, witnessed the beatings and was then taken away. For Hussainyar, that separation was worse than the whip, and for the next five weeks he constantly prayed for Farid's life. Not all members of the Taliban were cruel, he recalls. "Once I overheard an argument," he says. "A guard was saying to another that it is not right to beat simple porters and workers." But others enjoyed their work; one of the more zealous beat a man to death, continuing to flog him long after the screaming had stopped.

It took two months for Hussainyar's relatives to secure his release for $900. They also located Farid, who had been moved to a labour gang. His release cost another $1,200. They then trekked the 500 km on foot and by truck along mountain roads to Turkmenistan.

Photo: Clive Shirley Life is grim in refugee camps on Afganistan's border The Hazaras lives began to change for the better a year ago when Francoise Muller-Lauritzen, head of the office of the United Nations High Commission for Refugees in Ashgabat, was reviewing case files of the 2,000 Afghani refugees under her jurisdiction. She discovered that some had relations in Canada -- 15 years ago, she says, an initial contingent of Afghani Hazaras arrived in Quebec, assisted by the Aga Khan Foundation, which represents Shiite Muslims around the world. They were now able to sponsor their relatives in Ashgabat, and 94 were selected to come. "This group of Ismaili Hazara," says Muller-Lauritzen, "have many relatives already established and working for years in Canada. This is the best option for them."

In the classroom in Ashgabat, the question "what do you think life will be like in Canada?" draws a blank. While they will receive housing assistance and welfare for one year, all the newcomers know about Canada is that it's cold. But they believe that when their families are united and they are working, life will be better. "All the men are ready to work hard at any job," says Haidary. "It is our children who will prosper."

With their new homes, says Feraidon Kamaluddin, comes great responsibility. His father was taken by the Taliban in 1998 and has not been seen since, but the rest of the family managed to escape, Kamaluddin to Turkmenistan and his mother and brothers to Rawalpindi in Pakistan. "Their situation is terrible," he says. "I will send 50 per cent of everything I earn to my mother." Kamaluddin speaks for many when he says, "I trust in God, I trust in my relatives and I trust that the Canadian government will help us get on our feet. We will work hard and life will be good." At long last.

Source:Maclean's Magazine

RELATED LINKS:

Mowlana Hazar Imam gives Didaar to Syrian Jamaat

Mowlana Hazar Imam gives Didaar to Tajikistan Jamaat

Composition of People in Afghanistan at UK Government site

Nasir Khusraw Poetry Hero from Afghanistan

Ramadan and Eid ul Fitr Page Ramadan and Eid Mubarak!

More Nasir Khusraw Poetry

| Present Imam Shah Karim Aga Khan IV| 48th Imam Mowlana Sultan Mahomed Shah Aga Khan III | Hazrat Ali | Prophet Muhammad | Ismaili Heroes | Poetry | Audio Page | History | Women's Page | Legacy of Islam | Current Events |