The Tolerance of the Fâtimids toward “The People of the Book” (Ahl Al-Kitâb)

By Diana Steigerwald

“The first principle is to comprehend, to be convinced of, to uphold the fact

that there is no conflict between Islam and Christianity. There may be

conflict on political issues, there may be conflict on economic issues, there

may be conflict on social issues but the faith of Islam is not in conflict with

the faith of Christianity and that is so clearly specified in Islam and all I need

to do this morning is to mention the words to you Ahl al-Kitâb, the People of

Book. The Book is Allah’s revelation to man, revealed to man through

Allâh’s Prophets of which Prophet Muhammad was the last Prophet.” (Karîm

Âghâ Khân, Los Angeles, June 15, 1983)

In the Qur’ân, Jews and Christians are designated as Ahl al-Kitâb (People of the

Book). The Book (Kitâb) refers to previous revelation such as the Torah (Tawrât), the

Psalms (Zabûr), and the Gospels (Injîl). The status of Ahl al-Kitâb is distinguished from

the one of idolaters (mushrikûn) (XXVII: 62s.). The latter are invited to adopt Islâm

whereas Jews and Christians may keep their religion. The Qur’ân (III: 110, 199)

recommends Muslims to be respectful toward Ahl al-Kitâb since there are sincere

believers among them.

Islâm is a tolerant religion. Tolerance does not mean a passive adherence to all

opinions, but an affirmation of our own faith while respecting other religions. Tolerance

means to accept other people with their own differences, hence the Qur’ân recognizes the

right of People of the Book to practice their religion. It is clearly indicated in the Qur’ân

(II: 256) that Islâm may not be imposed by force because it is essentially tolerant.

Tolerance invites people to reflect and to dialogue in order to raise their level of

consciousness. Prophet Muhammad used to explain that the People of the Book received

only a part of the truth (III: 23; IV: 44). Hence certain Jews and Christians forgot the

original principles of the Abrahamic faith. Muhammad considers the religious writings

compiled by some scribes corrupted and falsified, each time that they do not agree with

the Qur’ânic truth (cf. XX: 133; IX: 30-31). Thus he invited the Jews and the Christians

to accept the Qur’ân which completes former revelations. People of the Book should find

the confirmation of the Qur’ânic revelation by carefully examining the Bible (cf. II: 89,

101; III: 7, 64; IV: 47). Even if the Judeo-Christian scriptures were altered, there still

remain some elements of truth within them. The Qur’ân even recognizes that certain Jews

and Christians are saved in the hereafter (II: 62).

The Constitution of Medina protected Jews and Christians. They were called

dhimmiyyûn (protected subjects) who were not subject to the religious tax (zakât) but

were required to pay another tax (jiziya). Their goods were protected and they were given

the right to practice their religion. In exchange for upholding certain obligations, they

were given these rights. The Constitution stipulated that the Jews would form one

composite nation with the Muslims; they could practice their religion as freely as the

Muslims; they had to join the Muslims in defending Medina against all enemies.

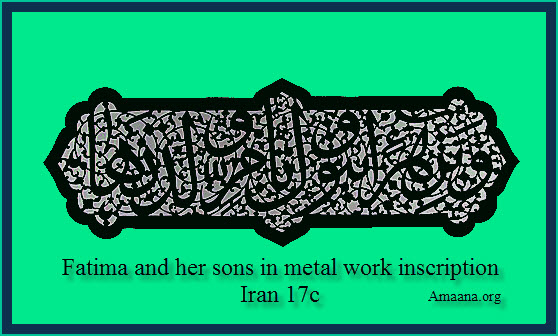

After the death of the Prophet, his direct descendants through his daughter Fâtima

and his cousin ‘Alî, had to wait many centuries before creating in 567/909 the Fâtimid

Empire, which extended from actual Palestine to Tunisia. In this Empire, the majority of

Muslims were Sunnî and Coptic Christians constituted a very significant portion of the

population. There also were some Orthodox Greeks called Melkites and Jews especially

in Syria. Nâsir-i Khusraw (d. circa 470/1077), the famous Ismâ‘îlî thinker, who visited

Egypt, noticed that nowhere in the Muslim world had he seen Christians enjoy as much

peace and material wealth as did the Copts. The Caliph Mu‘izz was the first to hire a

large number of Ahl al-Kitâb as administrators of the state. The Caliph al-‘Azîz continued

his father’s policy of religious tolerance and married a Melkite Christian. Al-‘Azîz’s two

brothers-in-law, Orestes and Arsenius, were nominated Patriarch of Jerusalem and

Metropolitan of Cairo, respectively. In spite of Muslim discontent and jealousy, al-‘Azîz

permitted the Coptic Patriarch Ephraim to restore the Church of St. Mercurius near

Fustât. Moreover, he protected the Patriarch against Muslim attacks.

The Caliph al-Hâkim (d. 411/1021) experienced many difficulties internally as well

as externally during his reign. He temporarily adopted some antagonistic measures

against Christians. Christians and Jews were forced to follow the Islâmic law. However,

toward the end of his reign al-Hâkim changed his policy. Thus he restored some of the

churches and became more tolerant toward the Christians and their religious practices.

Then Caliph al-Zâhir (d. 427/1036) who followed him, established a complete policy of

religious freedom.

During the Fâtimid period, Christians and Jews had full liberty to celebrate their

festivals. Muslims took part in these celebrations and the state participated as well. The

government also used some Christian festivals as an occasion for the distribution of

garments and money among the people. Christians and Jews were employed in the

Fâtimid administration. They were able to reach very important ranks, even to go as high

as the position of vizirate. It is worth mentioning that no similar examples of employment

of non-Muslim viziers are known among other Muslim contemporary dynasties. Nowhere

in the Muslim world during that time could non-Muslims accede to such a rank.

The only exception to this policy of religious freedom was under al-Hâkim’s reign.

According to the historian al-Maqrîzî (d. 846/1442), economic and social life deteriorated

during this era. The Ismâ‘îlî dâ‘î Hamîd al-dîn Kirmânî (d. 412/1021), in his treatise Al-

risâlat al-wâ‘iza, described this critical period in which there was a great famine. Several

of the hostile but temporary measures taken by al-Hâkim can be explained by the existing

situation, in which Sunnî Muslims were extremely perturbed by the growing prosperity of

Ahl al-Kitâb and their increasing power in the state. Al-Hâkim perhaps also wanted to

thwart the Byzantine Empire, which threatened Northern Syria. Broadly speaking, it must

be emphasised that Muslims, Jews, and Christians lived peacefully and worked together

for the well being of the Empire in all Ifrîqiya.

Even if today the actual Imâm Karîm Âghâ Khân is not the head of a state in

Aiglemont, he still employs in his service skillful people who are not Muslims. He

benefits from the competence of people coming from different cultures and religions. In

many of his speeches, he recognizes that the Western ethical principles of faith are

essentially the same as those found in Islâm.

In the rest of the Islâmic world, the treatment of the Ahl al-Kitâb varies from one

Muslim country to another. Most of the Muslim States are proclaimed secular, their

understanding of the relations between Muslim and non-Muslim is still inspired by the

previous juridical tradition, and their constitutions stipulate that the Chief of the state

must be Muslim. Today in Pakistan, Bangladesh, Iran, and in some other states, religious

minorities are represented in Parliament.

Bibliography:

Madelung Wilferd, “Ismâ‘îliyya”, EI2, vol. 6 (1978): 198-206.

Steigerwald Diana, L’islâm: les valeurs communes au judéo-christianisme, Montréal-

Paris: Médiaspaul, 1999.

Vajda Georges, “Ahl al-kitâb”, EI2 , vol. 1 (1979): 264-266.

Diana Steigerwald

Religious Studies, California State University (Long Beach)