Understanding the Quran

— Diana Steigerwald

California State University (Long Beach)

‘I believe in one God, and Muhammad, an Apostle of God’ is the simple and invariable profession of Islām. The intellectual image of the Deity has never been degraded by any visible idol; the honor of the Prophet has never transgressed the measure of human virtues; and his living precepts have restrained the gratitude of his disciples within the bounds of reason and religion. (Gibbon and al., 54)

There will come a time when nothing will remain of the Qur’ān but a set of rituals. And nothing will be more common than attributing falsities to God and the Prophet. — ‛Alī Ibn Abī Tālib

The Qur’ān contains a powerful message which generates a material and spiritual response. From its original source, the Mother of the Book (Umm al-Kitāb) came down to convey all humans to its universal message. It was revealed in fragments of varying lengths over twenty-three years, and every sūra was not only related to the overall Divine plan but also to emerging situations. Madinian sūras are generally the longer ones; the difficulty of rearranging them in chronological order was increased by the fact that most Madinian and many Makkan sūras were composite, containing discourses of different periods bound up together. Apart from the relatively few allusions to exactly date historical events, the principal evidences were supplied by general criteria of style and content. (Gibb, 36)

The collation of the Qur’ān began at the death of the Prophet in 632, but even during his life some verses were written down. Partial compilations were made on rather unsatisfactory materials (bones, leather sheets, stones etc.). The dying off of the companions of the Prophet, and the sharpening of a debate among surviving Muslims pushed the third caliph, ‛Uthmān (d. 35/656), to gather the Qur’ānic revelation into a single compilation called mushaf. The collection was declared complete and closed; the text was established by the Caliph ‛Uthmān and his entourage; and the other compilations were destroyed to avoid feeding dissent about the authenticity of the official Qur’ān.

For Muslims, Allāh speaks directly to humankind in the first person in the Qur’ān. Its literary style and diction are altogether different from the sayings (ahādīth) of the Prophet Muhammad. To those who doubt its Divine origin, the Qur’ān throws a challenge asking them to imitate its full text, or even to produce one sūra similar to it. Most Muslims believe that the ‛Uthmānic Codex contain integrally the truly Word of God.

As professor Mohammed Arkoun remarked, modern historians have examined the chronological order of the ‛Uthmānic Codex with critical rigor, principally because the Qur’ān was assembled in a very troubled political climate. Theodore Nöldeke (1836-1930), a German Arabist, carried out the first critical examination of the Qur’ān around 1860. Régis Blachère (1900-1973), a French scholar, refine this methodology by proposing a chronological order for the sūras, an issue that had preoccupied Muslim jurists (fuqahā’) seeking to identify which verses abrogated others (al-nāsikh wa al-mansūkh). “It is unfortunate that philosophical critique of sacred texts —which has been applied to the Hebrew Bible and to the New Testament without thereby engendering negative consequences for the notion of revelation— continues to be rejected by some Muslim scholars.” (Arkoun, 35) The works of the German school continue to be ignored, and most Muslims do not rely upon such research even though it would strengthen the

scientific foundations of the history of the ‛Uthmānic Codex and Islamic theology. Through various verses the Qur’ān discloses its full message and reveals its different stages of transmission. Some linguistic, grammatical subtleties, and semantics of the Qur’ān show its long elaboration and maturity.

Critical Reflections on the Qur’ān

This last decade, heated debates between the Western and Muslims scholars occurred on the question of the veracity of the Qur’ān and Islam itself. A review of the content demonstrates that the issue raises intense emotions, and sometimes do not promote good communal relations, or useful academic dialogue. It is important to understand how the compilation of the Qur’ān was established. The early Sunnī-Shī‛ī dispute engendered the division of Islam into two major branches leading over time to different ways of approaching the Qur’ān. At the end of the reign of the third Caliph ‛Uthmān (d. 35/656), it became evident to some members of the community that there were too many variations in the memorized texts. In 634, many of the memorizers (qurrā’) of the Qur’ān lost their lives in a battle against a rival community at Yamāma in Arabia. Fearing that the complete Qur’ān would be lost, the first Caliph Abū Bakr asked ‛Umar and Zayd b. Thābit to record any verse or part of the revelation that at least two witnesses testified at the entrance of the Mosque in Medina. All of the material gathered was recorded on sheets of paper, but was not yet compiled as a volume. These sheets were transmitted from Abū Bakr and ‛Umar to ‛Umar’s daughter Hafsa who gave them to ‛Uthmān who had them put together in the form of a volume. ‛Uthmān sent several copies of his compilation to different parts of the Muslim world and he then ordered that any other compilations or verses of the Qur’ān found anywhere else be burned. The ‛Uthmānic text was completed some twenty years after Muhammad’s death but it

was only a consonantal text. The final vocalized text of the Qur’ān was only established in the first half of the tenth century. Some scholars engaged in the search for the historical Qur’ān have questioned the authenticity of the ‛Uthmānic edition of the text and some have been guided by what the early Companions and Muslim scholars say about its compilation. The major issue in these debates was whether the ‛Uthmānic text comprehended all the Qur’ānic verses revealed to the Prophet, or whether there had been further verses missing from the text.

Very early Muslim scholars were trying to solve inconsistencies affecting a variety of legal injunctions in the Qur’ān. In order to resolve the differences of regulation found in disparate verses, they developed an intra-Qur’ānic theory of abrogation that substituted the legislative authority of an earlier Qur’ānic verse with that of a later one. Other Muslim scholars developed a criterion, called “the occasions of the revelation,” that connected some Qur’ānic verses with extra-Qur’ānic tradition to explain the context in which the verses were revealed. Both approaches to the Qur’ān concentrate their analysis on individual verses, rather than considering each Qur’ānic chapters as integral units. Other Muslim scholars in later medieval times based their approach to the Qur’ān on the assumption that each individual chapter formed original units of revelation and could only by divided be the place they were revealed “Meccan” and “Medinan.” (Böwering 2003: 349)

From the mid-nineteenth century, Western scholars began literary research on the Qur’ān, bringing together the findings of Muslim scholarship with the philological and text-critical methods inspired by biblical scholarship just beginning in Europe. The Western scholars were mainly trying to establish a chronological order of Qur’ānic chapters and passages that could be related with the main events in Muhammad’s life. This Western chronological approach to the Qur’ān reached its peak in the work of Theodore Noeldeke, which was then challenged by Richard Bell, and was completed by Rudi Paret’s manual of commentary and concordance to the Qur’ān. It largely adopted the traditional distinction between Meccan and Medinan suras, yet subdivided the Meccan period of Muhammad’s revelation into three distinct periods, with the Medinan period as the fourth. These scholars were relating Qur’ānic passages to historical events known from extra-Qur’ānic literature while systematically analyzing their philological and stylistic nature (Böwering 2003: 349-350).

A Muslim backlash has not deterred the critical-historical study of the Qur’ān, as the collected essays published in The Origins of the Koran (1998). This book, edited by an unknown author Ibn Warraq (neither his full name nor his institutional affiliation are mentioned in the book), consists of thirteen previously published essays on the history and nature of the Qur’ānic text, twelve of them were published between 1890 and 1940 and only the thirteenth was published in 1985. Patricia Crone, an uncommon scholar, wrote with Michael Cook, Hagarism: The Making of the Islamic World (1977) making controversial claims about the origins of Islam and the writing of Islamic history.1 The arguments put forwards in Hagarism came under immediate attack, from Muslim and non-Muslim scholars alike, for its heavy reliance on hostile sources. A harsh protest came in 1987, in the Muslim World Book Review, in a paper titled “Method Against Truth: Orientalism and Qur’anic Studies,” by the Muslim critic S. Parvez Manzoor.

There are considerable divergences among specialists. Günther Lüling (1973) affirmed that “The text of the Qur’ān as transmitted by Muslim Orthodoxy contains, hidden behind it as a ground layer and considerably scattered throughout it (together about one-third of the whole Qur’ān text), an originally pre-Islamic Christian Text.” (Lüling, 1) Lüling wants to demonstrate that the ‛Uthmānic codex is not the real Qur’ān revealed to Muhammad. For him, the doctrine included in the real Qur’ān should have been closer to pre-Islamic Jewish and Christian texts. Unfortunately there is not enough Arabic, Syriac or Aramaic published texts (on pre-Islamic Jewish and Christian manuscripts) which can back up and legitimate his thesis. Many pre-Islamic Judaic and Christian texts are not available and most of them are unknown or not yet edited in a scholarly manner, therefore their authenticity is not yet validated. All these preliminary researches need to be done in order to be able to compare rigorously the author’s assumptions.

— 1 Their controversial claims were: i) the text of the Qur’ān did not reach its final form before the last decade of the seventh century; ii) Mecca was a secondary sanctuary; iii); the migration (hijra) of Muhammad and his followers

from Mecca to Medina in 622, may have evolved long after Muhammad’s death etc. —

Presently the thesis of Lüling is highly speculative, the work done by the author seems to be a premature work. John Wansbrough (1977) believe the Qur’ān was not compiled until two to three hundred years after Muhammad’s death while John Burton (1977) argued that Muhammad himself had already established the final edition of the consonantal text of the Qur’ān.

Christoph Luxenberg, a pseudonym used by the author (2000), basing himself on obscure Qur’ānic passages, seeks to prove that the consonantal text of the ‛Uthmānic version was misread by the early Muslim generations. According to Luxenberg, the language of the Qur’ān was profoundly influenced by Syriac, the written language common in the Middle East used long before Arabic was committed to writing. He looks for Syriac words in the Arabic of the Qur’ān and analyses their meaning in various verses. “This results in some astonishing readings, which appear plausible at times when elegant solutions are suggested for Qur’ānic phrases that experts are unable to render with certitude, or startling at other times, for example when the heavenly virgins are banished from the Qur’ān by the substitution of grapes as fruits of Paradise.” (Böwering 2003: 353)

Despite such resistance, Western researchers with a variety of academic and theological interests press on, applying modern textual and historical analysis to the study of the Qur’ān. Brill Publishers have decided to publish the first-ever Encyclopaedia of the Qur’an. The general editor of the encyclopaedia, Jane McAuliffe, a professor of Islamic Studies at the University of Toronto was hoping that it will be analogous to biblical encyclopaedias and will be a comprehensive work for the Qur’ānic scholarship. The Encyclopaedia of the Qur’an is a collaborative compendium, carried out by Muslims and non-Muslims. This encyclopaedia, published by Brill combines alphabetically-arranged articles about Qur’ānic terms, concepts, personalities, place names, and cultural history with essays on the most important themes in the Qur’ān. So far four volumes have been published: volume one (A-D) in 2001, volume two (E-I) in 2002, volume three (J-O) in 2003, volume four (P-Sh) in 2005. Recently Andrew Rippin has edited The Blackwell Companion to the Qur’ān. (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2006) which comprises various chapters written by renowned specialists; this book will be useful for students as well as scholars in the field.

The nature and the content of the Qur’ān

It is equally important to understand how Muslim believers view the Bible through the lens of the Qur’ān, and in their estimation their Holy Book is the only Scripture preserved in its authenticity. Muslims believe in previous revelations at least those mentioned in the Qur’ān. The oral traditions (ahādīth) played an important role in preserving the proper interpretation of the Qur’ānic text. It is generally believed that Muhammad acquired his biblical knowledge mainly through oral tradition in his mother tongue. This oral wisdom came from Syriac, Aramaic, Ethiopian, and Hebrew materials, since there are many foreign words in the Arabic Qur’ān. In Christianity, the role of the Bible is secondary to that of Christ; it witnesses to Him and His actions. The Christians develop a personal relationship with Jesus living a Christocentric experience. Islam, by contrast, centres on the Qur’ān which is its “raison d’être.” The Qur’ān isthe Divine revelation which instructs men how to live according to the will of God. The understanding of the Qur’ān as a perfect and inimitable in message, language, style, and form — referring to the preserved Tablet (Lawh-i mahfūz) or celestial Qur’ān — is strikingly similar to the Christian notion of the Bible’s “inerrancy” and “verbal inspiration” that is still common in many places today.

The Qur’ān is thus also known as al-Furqān, literally, “the discernment,” which enables man to distinguish between good and evil. The Book is known also as al-Hudā, the Guide, since it contains the necessary knowledge to remain upon the straight path (al-sirāt al-mustaqīm) and become aware of God’s Will. Moreover, for Muslims, the Qur’ān is the Umm al-Kitāb, the Mother of the Book, since it is the prototype of all books, the archetype of all things, and the root of all knowledge. It is important to distinguish between the Qur’ān and its translation. For Muslims, the Divine Word assumes a specific Arabic form, and that form is as essential as the meaning that the words convey. The Qur’ān cannot be translated adequately into any other language. Hence only the Arabic Qur’ān is the Qur’ān, and translations are simply limited and partial.

Exhortations to observe the nature, to reflect upon Allāh’s creation, to study and draw lessons from the history of past nations and civilisations are all disclose to man to strengthen his real convictions. The Qur’ān gives insight into some natural phenomena, to give a few illustrations: it alludes to the sphericity and revolution of the earth (XXXIX: 5) and describes the formation of rain (XXX: 48); fertilisation by the wind (XV: 22); the revolution of sun, moon, and 6 planets in their fixed orbits (XXXVI: 36-40); the aquatic origin of all living creatures (XXI: 30); the duality in the sex of plants and other creatures (XXXVI: 35-36); the bees’ mode of life (XVI: 68-69); and the successive phases of the child in his mother’s womb (XXII: 5; XXXIII: 14). Its central spiritual theme converges on the fact that man has misled himself by following his desires based on superficial observations. The straight path has been pointed out to men again and again by the Prophets in all ages. The teleological purpose of the Qur’ān is to invite man to follow the Divine Guidance.

Variant readings are also an interesting feature of the Qur’ān. One tradition for example linked this feature to seven different ways to recite the text, even if it is generally not accepted. At the time of the Prophet, Arabs spoke many different accents and many of them did not know how to read or write. Other differences include variant readings of words which can be read as either singular or plural in the unvowelled text or in different wordings. The Muslim scholars point out that the script used had no diacritical points; each word could be read in various ways. This difference in recitation was later to lead to conflict between Syrians and Iraqis, and this led later Muslims to standardise the Qur’ānic text. Muslims have disagreed over the exact interpretation of Qur’ānic verses as much as followers of other religions have over their own scriptures. One of the sources of the rich Islamic intellectual history comes from the variety of interpretations provided for the same verses. Some Muslim thinkers often quote Prophetic traditions to the effect that every verse of the Qur’ān has seven meanings, beginning with the literal sense, and as for the seventh and deepest meaning, God alone knows that and those who are firmly rooted in knowledge (al-rāsikhūn fī al-‛ilm) (III: 5-7). The language of the Qur’ān is anagogic — each word shows the richness of the Arabic language. Naturally people grasp different meanings from the same verse. “The richness of Qur’ānic language and its receptivity toward different interpretations help explain how this single book could have given shape to one of the world’s great civilisations. […] The Book had to address both the simple and the sophisticated, the shepherd and the philosopher, the scientist and the artist. […] Islam did in fact spread very quickly to most civilisations of the world, from China and Southeast Asia to Africa and Europe. […] The Qur’ān has been able to speak to all of them because of the peculiarities of its own mode of discourse.” (Sachiko Murata and William C. Chittick, XV – XVI)

The Qur’ān as the source of guidance for Muslims

Far from being an obstacle to the spread of Islam, the Arabic language unites all Muslims. Even though the text was fixed, the meaning was left to fluidity and adaptability. People who did not know Arabic were encouraged to learn the Arabic text and then understand it in terms of their own cultural and linguistic heritage. But no one’s interpretation could be final. From one generation to the next, each Muslim needs to establish his or her own link with the Divine scripture.

For Westerners, it is extremely fastidious to read the Qur’ān, especially in translation. Major barriers remain that prevent an appreciation of the Qur’ān by non-Muslims or by those who do not have a thorough training in the Arabic language and religion. Even such training does not guarantee access to the book. According to Muslims, the Qur’ān is inimitable (i‛jāz) and unsurpassable not only in the grandeur of its diction, the variety of its imagery and the splendour of its words painting, but also in its substantial meaning and profundity. To disclose the spiritual significance of the Qur’ān, it is essential to remember that the Qur’ān was a sonoral revelation. The first words revealed by Gabriel surrounded the Prophet like an ocean of sounds. The sounds of the Qur’ān reverberate on the Muslim soul even before it appeals to his mind. The Qur’ān is thus the very first sound that welcomes the Muslim into the first stage of his journey on earth. And it is the Qur’ān that is chanted at the moment of death and accompanies the soul in its posthumous journey back to the Divine Presence.

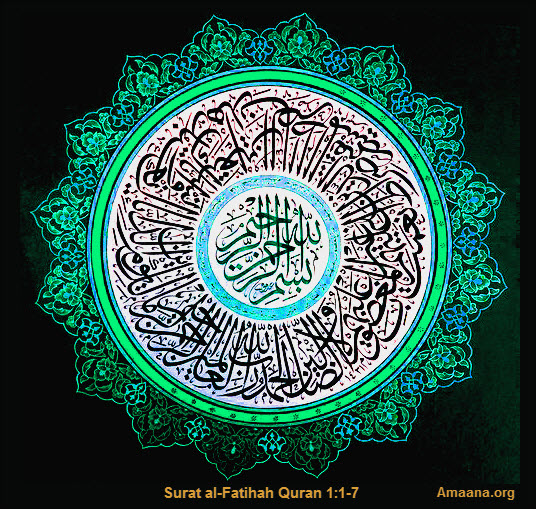

The writing of the Qur’ān is the sacred art of Islam. The Muslim calligraphy, which is so central to Islamic civilisation, is inseparable from the Qur’ān. To understand the reverence that Muslims show toward the Qur’ān, it is necessary to take into account the spiritual meanings of the calligraphy of words and the sounds that surround and penetrate man when the text is recited. Instinctively every faithful feels this powerful Divine Presence and finds comfort and protection in the reflection over the meaning of the Qur’ān. (Nasr, 5)

The Qur’ān appeals to the intellect of man. It encompasses all the creation, the Day of Judgement (Yawm al-Dīn), and the Life Beyond. It establishes a metaphysical link between man and God. Not only the supreme doctrine of Unicity (Tawhīd) but all Islamic doctrines are rooted in the Qur’ānic revelation. All branches of Islam whether Sunnī or Shī‛ī base their teaching upon the Qur’ān. Whether they agree or differ on the question of determinism and free will, the primacy of faith or action, or the relation of God’s Mercy to His Justice, they all derive their teachings from verses of the Qur’ān, which is like an ocean into which all streams of Islamic thought flow. (Nasr, 7-8)

Likewise, the practices of Muslims as ordained by the religious law (sharī‛a) have their origin in the Qur’ān. The elaboration of the sharī‛a depends, furthermore, upon consensus (ijmā‛) and analogical reasoning (qiyās), in principle all the sharī‛a has to derive from the Qur’ān. The other sources are only means of elaborating and making explicit what is already contained in the Qur’ān. The Qur’ān determines, for Muslims, all ethical norms and principles. What the Qur’ān teaches constitutes morality, not what human reason determines on the basis of its own judgements.

Shī‛ī interpretation of the Qur’ān

The first person to compile the Qur’ān after the demise of the Prophet was ‛Alī ibn Abī Tālib. He did so in accordance with the instructions and testament of the Prophet. He arranged the verses chronologically and described their context. According to many early transmitted reports, ‛Alī presented his compilation of the Qur’ ān to the companions; but they rejected it, so he took it back. These reports also pointed out that there were substantial differences between the various compilations of the Qur’ān. The only copy of the complete Qur’ān with verses proclaiming the exalted status of ‛Alī and the future Imāms, was in ‛Alī’s possession. ‛Alī, known for his vast knowledge of the Qur’ān, preserved this original copy of the Qur’ān and passed it on his Successors. In his codex of the Qur’ān he had reportedly indicated the verses, which were abrogated, and those, which abrogated them. (cf. Tawil in Twelver Shiism)

The Nizārī Ismā‛īlī al-Shahrastānī (d. 548/1153), the famous Muslim historian of religions, in his book Mafātīh al-Asrār wa-Masābīh al-Abrār, refers to a compilation (mushaf) of ‛Alī Ibn Abī Tālib. He writes that on the recommendation of Muhammad, ‛Alī had included some exegetical explanations in his compilation. ‛Alī then reprimands some Prophet’s companions who refused his compilation and then al-Shahrastānī reported the following:

After completing the funeral rites of the Prophet, he (‛Alī Ibn Tālib) took an oath not to wear a robe, except for attending the Friday prayers, until he compiled the Qur’ān; because he had been categorically commanded to do so. He then collected and compiled the Qur’ān in the order of its revelation without any tampering or addition or subtraction. The Prophet of Allah had earlier mentioned [to him] the order and the position of the verses and the 9 chapters of the Qur’ān as regards their sequence (Shahrastānī, Mafātīh al-Asrār wa-Masābīh al-Abrār, vol. 1, p. 5.)

‛Alī’s compilation comprised the main text and the commentaries within margins. (al-Shahrastānī, Mafātīh al-Asrār wa-Masābīh al-Abrār, vol. 1, p. 5.) And then al-Shahrastānī continues as under:

And it is said that after completing its compilation he took it to the people (the so-called elderly ashab) who had gathered in the Mosque. They carried it with difficulty and it is said that it was as large as a camel-load. The Imām announced to them: “This is the Book of Allah exactly as it was revealed to Prophet Muhammad and I have compiled it between two covers. They said: ‘Pick the mushaf and take it back with you, we are not in need of it.’ The Imām said: ‘By Allah, you will never see it again. Since I had compiled it, it was my responsibility to inform you about the compilation.’ He [the Imām] then returned home, reciting this verse: ‘…O my Lord! Surely my people have treated this Qur’ān as a forsaken thing’”. (25:30) (al-Shahrastānī, Mafātīh al-Asrār wa-Masābīh al-Abrār, vol. 1, p. 12

Another significant feature of the Mafātīh al-Asrār is that it quotes the sequence of the mushaf of Imām ‛Alī from Muqatil ibn Sulaymān (b. 150 AH). Al-Shahrastānī reported the event of Ghadīr Khumm; according to Shī‛ites, Islām reached its perfection when Prophet Muhammad revealed the religious mission of his cousin and son-in-law ‛Alī ibn Abī Tālib:

Of whomsoever I am the Master (Mawlā), ‛Alī is the Master (man kuntu mawlāhu fa-‛Alī-un mawlāhu). May God befriend those who befriend him, and be an enemy to those who are enemies to him; may he assist those who assist him, and forsake those who forsake him. May the Truth be with him wherever he goes. So, I have delivered [the message]. (Shahrastānī, 140)

Prophet Muhammad is reported to have said: “I am from ‛Alī and ‛Alī is from me.” On another occasion of the historic Mubāhala, he apparently declared: “‛Alī and I are one and the same Light.” (Corbin, 62) Classical Shī‛ī doctrine holds that ‛Alī and the succeeding Imāms received inspiration (ilhām) from God. But it is only the legislative Prophecy which came to an end, the guidance of humanity must continue under the Walāya (Institution of the Friends of God) of an esoteric Prophecy (Nubuwwa bātiniyya). Thus ‛Alī, the first Imām, is designated as the foundation (asās) of Imāma. He is the possessor of a Divine Light (Nūr) which is transmitted

after his death to his Successor.

The Ahl al-Bayt (the People of the House [of Muhammad]) and the Qur’ān are “two inseparable entities (al-Thaqalayn)” guiding all the Muslim community (umma). During the expedition of Tabūk, Prophet Muhammad declared: “You (‛Alī) are to me what Aaron was to Moses except that there will be no Prophet after me.” (Jafri, 18) The inclusion of Fātima in the Ahl al-Bayt (XXXIII: 33) is by virtue of her unique position, being the daughter of the Prophet, the wife of the first Imām, and the “Mother” of all Imāms, she establishes the link between Prophecy (Risālat) and divine Guidance (Imāma). For Sunnī Muslims, the Ahl al-Bayt include only the wives of the Prophet while for Shī‛ites, they comprise ‛Alī, Fātima, Hasan, Husayn, and their direct descendants designated by nass (appointment). Wilferd Madelung makes the following remark on the verse of purification (tathīr) (XXXIII: 33) concerning the “five People of the Mantle”: “Who are the ‘People of the House’ here? The pronoun referring to them is in the masculine plural, while the proceeding part of the verse is in the feminine plural. This change of gender has evidently contributed to the birth of various accounts of a legendary character, attaching the latter part of the verse to the five People of the Mantle (Ahl al-Kisā’): Muhammad, ‛Alī, Fātima, Hasan, and Husayn. In spite of the obvious Shī‛ite significance, the great majority of the reports quoted by al-Tabarī in his commentary on this verse support this interpretation.” (Madelung, 14-15.)

Most sources agree that ‛Alī was a profoundly religious man, devoted to the cause of Islām and the rule of justice in accordance with the Qur’ān and the Sunna.

The unbelievers say: “No apostle art thou.” Say: “Enough for a witness between me and you is God, and the one who has knowledge of the Book.” (XIII: 43)

Who is this person “who has knowledge of the Book”? According to some traditions, it refers to ‛Alī ibn Abī Tālib. (Sunnī reference, see al-Suyūtī, vol. 4, 669; and for a brief review see al-Tabātabā’ī, vol. 11, 423-428.)

In a Hadīth Qudsī, Allāh said: “I am the city of Knowledge (‛Ilm) and ‛Alī is its Door (Bāb).” Muhammad also said: “‛Alī is the best of all judges of the people of Madina and the chief reader of the Qur’ān.” The Imām is the “Inheritor” and “Treasurer” of the Knowledge of God, these qualifications are based on the following verses of the Qur’ān (al-rāsikhūn fī al-‛ilm III: 5-7; LXXII: 26-27; III: 179). The Knowledge of the Unseen (‛Ilm al-Ghayb) is also a key concept in Shī‛ism which unables the living Imām to explain and actualise the meaning of the Qur’ān according to the new Era. The following verses clarify this concept “He [alone] knows the Unseen (Ghayb), nor does He make any one acquainted with His Mysteries, – Except an apostle whom He has chosen: and then He makes a band of watchers march before him and behind him.” (LXXII: 26-27) “God will not leave the believers in the state in which ye are now, until He separates what is evil from what is good nor will He disclose to you the secrets of the Unseen (Ghayb). But He chooses of His Apostles [for the purpose] whom He pleases. So believe in God and His apostles: And if ye believe and do right, ye have a reward without measure.” (III: 179) According to Shī‛ī traditions, Imām ‛Alī was blessed with the ‛Ilm al-Ghayb because he had the full knowledge of the Qur’ān as described by verse XIII: 43 discussed previously. On this basis, ‛Alī is believed to inaugurate the universal Imāma. Moreover, according to Shī‛ī traditions (ahādīth), the Prophet had conveyed all his knowledge to ‛Alī who gave it to his progeny (Ahl al-Bayt).

Esoteric commentary on the Qur’ān

The Qur’ān is the source of not only religious law (sharī‛a) but also of spiritual quest. The spiritual life of Islam as it was to crystallise later in the Sūfī orders goes back to the Prophet, who is the source of spiritual virtues found in the ideal Muslim soul. But the soul of the Prophet was itself illuminated by the Light (Nūr) of Allāh as revealed in the Qur’ān, so that quite justly one must consider the Qur’ānic revelation as the origin of Sūfism. The Sūfīs have been the foremost expositors and commentators upon the Qur’ān and that some of the greatest works of Sūfism such as the Mathnawī of Jalāl al-dīn Rūmī (d. 672/1273) are in reality commentaries of the Qur’ān.

The spiritual exegesis requires a great deal of training to enter into the Qur’ānic discourse. Moreover, this training is accompanied by the embodiment of the Qur’ān through recitation and ritual. The Qur’ān possesses an innate power to transform those who try to approach it on its own terms. This is precisely what Islām is all about — submission to Allāh — it is a submission firmly grounded in real faith (imān). The Qur’ān has an inner dimension like the soul which gives life to the body. The esoteric meanings of the Qur’ān cannot be comprehended directly through human thought alone. Only Allāh and those firmly grounded in knowledge (al-rasikhūn fī al-‛ilm) can give the spiritual exegesis (ta’wīl) of the Divine revelation. “It is to cause something to arrive at its origin. He who practises ta’wīl, therefore, is someone who diverts what is proclaimed from its external appearance (its exoteric aspect or zāhir), and makes it revert to its truth, its haqīqa.” (Corbin, 12)

Beyond the rules and regulations which are related to the material life and are relevant only for a certain period of time, we must understand the spirit of Islam and look for the genuine Qur’ān. The precepts of Islam must not be interpreted as unalterable dogmas; as circumstances change, they must be replaced with new precepts more compatible with Islam’s ideal society. The Qur’ān is a dynamic revelation which claims to respond to the problems and needs of humankind and society in any circumstances. When Muslims fail to perceive the dynamism of the Qur’ān, it inevitably leads to retrogression, oppression and discrimination in the name of Islam. In the Qur’ān all human beings are equal, regardless of gender, race or nationality. Allāh is the only One who knows how to differentiate between Muslims according to their degree of piety (taqwā) and righteousness (XLIX: 13)

We may end this chapter by quoting the striking hadīth attributed to Prophet Muhammad: “Everything has a heart and the heart of the Qur’ān is the sūra Yā-Sīn (XXXVI); and he who reads it, God will write for him rewards equal to those for reading the whole Qur’ān ten times.” (Hughes, 521) The Qur’ānic science is divided into many fields. The exegetical tradition of the Qur’ān played important weight in the Muslim world throughout history; its exegesis is not limited to the various schools of Qur’ānic commentators, but is found in almost every kind of literature.

Bibliography

Qur’ān translations:

The Holy Quran. Text, translation and commentary by Abdullah Yusuf Ali. Elmhurst, N.Y.: Tahrike Tarsile Qur’an, Inc. ; Scarborough, Ont. : Mihrab Publishers & Book DistributorsCanada [distributor], 1987.

The Koran Interpreted. Translated by Arthur J. Arberry. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982.

Selected studies:

Abu Al-Qasim Ibn Ali Akbar Khui, Prolegomena to the Qur’an, trans. by Sachedina, Abdulaziz Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Arkoun, Mohammed. Rethinking Islam. Translated and edited by Robert D. Lee. San Francisco: Westview Press, 1994.

Ayoub, Mahmoud. The Qur’an and Its Interpreters, vol. II: The House of Imran. Albany NY: State University of New York Press, 1992.

Baljon, J. M. S. (Johannes Marinus Simon) Modern Muslim Koran interpretation, 1880-1960. Leiden, E. J. Brill, 1961.

Bell, Richard. Bell’s introduction to the Qur’an. Completely revised and enlarged by W. Montgomery Watt. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, c1977, 1990.

Blachère, Régis. Introduction au Coran. Paris: Maisonneuve et Larose, 1991.

Böwering, Gerhard. The mystical vision of existence in classical Islam: the Qur’anic hermeneutics of the Sufi Sahl At- Tustari (d. 283/896). Berlin, New York: De Gruyter, 1980.

Böwering, Gerhard. “The Qur’ān as the Voice of God”. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. Vol. 147.4 (2003): 347-353.

Burton, John. The collection of the Qur’an. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977 Corbin, Henry. History of Islamic Philosophy. Translated by Liadain Sherrard and Philip Sherrard. London: Kegan Paul International, 1993.

Cook, Michael. The Koran: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Crone Patricia and Michael Cook. Hagarism: The Making of the Islamic World.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977.

Faruqi, Isma‛il. “Towards a New Methodology for Qur’anic Exegesis.” Islamic Studies (1962) pp. 35-52.

Gibb, Hamilton. Mohammedanism: An Historical Survey. New York: Mentor Books, 1953.

Gibbon, Edward and Simon Ockley. History of The Saracen Empires. London, 1870.

Gilliot, C. Exégèse, langue, et théologie en Islam: L’Exégèse coranique de Tabari. Paris, 1990.

Hughes, Thomas Patrick. Dictionary of Islam. New Delhi: Adam Publishers & Distributors, 2003.

Ibn Warraq (ed.). The Origins of the Koran: Classic Essays on Islam’s Holy Book. Amherst, NY:

Prometheus Books. 1998.

Izutsu, Toshihiko. God and Man in the Koran: Semantics of the Koranic Weltanschauung. (Tokyo, 1964).

Izutsu, Toshihiko. Ethico-Religious Concepts in the Qur’an. (Montreal, 1966). Revision of The Structure of the Ethical Terms in the Koran. Tokyo, 1959.

Jafri, Syed H.M. The Origins and Early Development of Shi‛a Islam. London: Longman, 1981.

Jeffery, Arthur. The Qur’an as scripture. New York: R. F. Moore Co., 1952.

Jeffery, Arthur. ed. Materials for the history of the text of the Qur’an : the old codices : the Kitab al-masahif of Ibn Abi Dawud, together with a collection of the variant readings from thecodices of Ibn Ma‛sud, Ubai, ‛Ali, Ibn ‛Abbas, Anas, Abu Musa and other early Qur’anicauthorities which present a type of text anterior to that of the canonical text of ‛Uthman. New York: AMS Press, 1975.

Lester, Toby. “What is the Koran?” The Atlantic Monthly, January 1998, vol. 283.1, pp. 43-56.

Lüling, Günter. A Challenge to Islam for Reformation: The Rediscovery and Reliable Reconstruction of a Comprehensive Pre-Islamic Christian Hymnal Hidden in the Koran under Earliest Islamic Reinterpretations. Delhi, Motilal Banarsidass, 2003; Book Review of Diana Steigerwald in Journal of the American Oriental Society. Vol. 124.3 (2004): 621-623.

Luxenberg Christoph, Die syro-aramaeische Lesart des Koran; Ein Beitrag zur Entschlüsselung

der Qur’ānsprache. Berlin: Das Arabische Buch, 2000.

McAuliffe, Jane Dammen, Claude Gilliot and William Graham (Ed.) Encyclopaedia of the

Qur’an. Vol. 1, Leiden: Brill, 2005.

Madelung, Wilferd. The Succession to Muhammad: A Study of the Early Caliphate. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Mir, Mustansir. Dictionary of Qur’anic terms and concepts. New York: Garland Pub., 1987.

Murata, Sachiko and William C. Chittick. Vision of Islam. St. Paul (Minnesota): Paragon, 1994.

Nasr, Seyyed Hossein, ed. Islamic Spirituality: Foundations. New York/London: Crossroad 1987.

Noldeke, Theodor. Geschichte des Qorans. Leipzig, 1909.

Nwyia, Paul. Exegese coranique et langage mystique: Nouvel essai sur le lexique technique des mystiques musulmans. Beirut, 1970.

Paret, Rudi. Der Koran: Kommentar und Konkordanz. Stuttgart, W. Kohlhammer, 1971.

Paret, Rudi. Mohammed und der Koran: Geschichte und Verkuendigung des arabischen Propheten. (Stuttgart: W. Kohlhammer, 1957.

Rahman, Fazlur. Major themes of the Qur’an. Minneapolis, MN: Bibliotheca Islamica, 1980.

Rippin, Andrew. ed. Approaches to the History of the Interpretation of the Qur’an. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988.

Seale, Morris S. Qur’an and Bible: studies in interpretation and dialogue. London: Croom Helm, c1978.

Al-Shahrastānī, Kitāb al-Milal wa al-Nihal, translated by A. K. Kazi and J. G. Flynn in Muslim Sects and Divisions. London: Kegan Paul International, 1984.

Al-Shahrastānī, Mafātīh al-Asrār wa-Masābīh al-Abrār. Library of the Consultative Islamic Assembly, Tehran, 1989.

Smith, W.C. “The True Meaning of Scripture: An Empirical Historian’s Nonreductionist Interpretation of the Qur’an.” IJMES (1980), 11, pp. 487-505.

Steigerwald, Diana. “‛Alī.” Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim World. Vol. 1 (2003): 35-38.

Steigerwald, Diana. “Ta’wīl in Ismā‛īlism.” In The Blackwell Companion to the Qur’ān. Edited by Andrew Rippin. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2006.

Steigerwald, Diana. “Ta’wīl in Twelver Shī‛ism.” In The Blackwell Companion to the Qur’ān. Edited by Andrew Rippin. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2006.

Al-Suyūtī, Jalāl al-Dīn. Al-Durr al-Manthūr. Beirut: Dar al-Fikr, n.d.

al-Tabātabā’ī, Muhammad Husayn. Al-Mizān. Beirut, 1973.

Wansbrough, John E. Quranic studies: sources and methods of scriptural interpretation. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977.

Watt, W. Montgomery. Companion to the Qur’an, based on the Arberry translation. London: Allen & Unwin, 1967.

ShukarAllah for Blessing mankind with Qur’an Al Karim, Our Beloved Prophets and Imams.

A very well researched relevant essay written by Diane Steigerwald. The Historical and researched facts relating to compilation of the Holy Qur’an is not discussed much by the practicing Muslim Ummah or their leaders and brief mention by the Muslim authors and that too ignoring the recent findings and hence the compilation done during Uthman’s time is accepted unquestioned…Hence an amnesia amongst Muslims to these researched findings that may be not what they want to know. Alas…Sad state existing even in the 21st century!!!

Good Article thanks for the post 🙂