On the Meaning of Music in Persian Mysticism

On the Meaning of Music in Persian Mysticism

By Henry Corbin

(Introduction given at le cité Universitaire May 19th 1967, on the occasion of an evening of Persian music, poetry and dance. L’Iran et la Philosophie, Fayard 1990. This translation appeared in Temenos 13, 1992, Translated by Kathleen Raine)

I would like to suggest, in a few pages, how I see the fact that among all the forms of mysticism our science of religions has made known to us, Persian mysticism is notable as having always tended towards musical expression, and as never having found its complete expression otherwise than in that form. The part played by music in Islamic countries has not, over the centuries, followed the same course as in the West; doubtless because those who condemned its use saw in it in nothing more than a profane diversion. By contrast, what our mystics have produced is in the nature of an equivalent of what we call sacred music; and the reason for this is so profound that, rightly understood, all music, provided it be devoted to its supreme end, cannot be seen as other than sacred music. But is that not another paradox?

I believe that every Iranian must remember, more or less, the famous prologue to

Jalaluddin Balkhi Rumi‘s

Mathnawi, more often known in Iran as Mowlânâ. This prologue perhaps serves to justify the paradox I have just stated. Of this I have been convinced by the recent discovery, in the course of my researches, of an eminent Iranian thinker, at present almost unknown to the general public, but who deserves, when the time comes, I truly believe, to figure in our anthologies of the history of philosophy and spirituality — I mean the 17th century Qazi Sa’id Qommi. In one of his great works, still in manuscript, this philosopher recalls, and comments at length on certain propositions of one who is equally dear to Iranian hearts, the first Imam of the Shi’ites,

Mowlana ‘Ali ibn Abi Talib. According to this tradition the first Imam said one day, in the presence of his friends:

‘Because in my heart there were anguishing cares which I was unable to find anyone in whom to confide, I struck the ground with the palm of my hand and confided my secrets to it, so that every time a plant germinates from the earth, that plant is one of my secrets.’ — Hazrat Mowlana Imam Ali

This is not a question, to be sure, of some secret of rural economy. The earth of which he speaks is not the earth under our feet and which is today in process of being devastated by the ambitions of our inordinate conquests. It is the ‘Earth of Light’ perceived only with the eyes of the heart. But it is for us — for each of us — to behold that Earth with eyes capable of seeing it and, so beholding it, to ensure that the ‘Earth of Light’ still matters to us, concerns us too. It depends on ourselves whether (striking the ground of that Earth of Light with the Imam) we see emerging certain plants which reveal to us our scarcely suspected secrets. And occupying a pre-eminent place among these plants the philosopher Qazi Said Qommi names the reed from which the mystic flute is cut, whose lament is breathed in the prologue of the Mathnawi, and of which we know that it is associated with the religious services of the Mowlana Order.

We have all heard chanted at least a few verses of that prologue:

Listen to the story told by the reed flute, of the partings whose lament it breathes,

Since I was cut from the reed-bed my plaint has made both men and women mourn their lot.

Whoever is parted far from his native place longs to return to the time of union.

My secret and my plaint are one, but both eye and ear lack light.

Body is not veiled from soul, nor soul from body; yet none is permitted to see the soul.

The sound of that flute is not a breath of wind, it is fire! He who has not that fire, let him be nothing! — Rumi

Certainly no-one has seen the soul with the eyes with which we normally perceive the things of this world. Only the lament of the mystic flute cut from the source, from the Earth of Light, can give some premonition of it. All that grows from that Earth and is separated from it, the story of exile and return, this it is that haunts the mysticism of Persia, something which can neither be seen nor proved by reason, which cannot be said or seen by direct vision, but of which musical incantation alone can give us a foretaste and make perceptible, insofar as it belongs to listening to music to make us suddenly into clairvoyants.

The unsayable which the mystic seeks to say is a story that shatters what we call history and which we must indeed call metahistory, because it takes place at the origin of origins, anterior to all those events recorded — or recordable — in our chronicles. The mystic epic is that of the exile, who, having come into a strange world, is on the road of homecoming to his own country. What that epic seeks to tell is dreams of a prehistory, the prehistory of the soul, of its pre-existence to this world, dreams which seem to us a forever forbidden frontier. That is why, in an epic like the Mathnawi we can scarcely speak of a succession of episodes, for all these are emblematic, symbolic. All dialectical discourse is precluded. The global consciousness of that past, and of the future to which it invites us beyond the limit of chronology, can only attain musically its absolute character. In order to have their ‘Holy Book’, that Mathnawi which is often called ‘the Persian Quran,’ the mystics are, essentially, obliged to sing in order to speak.

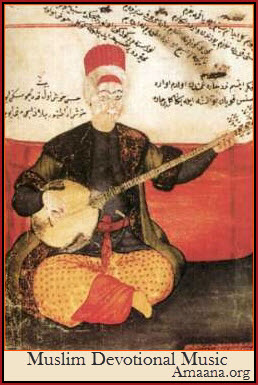

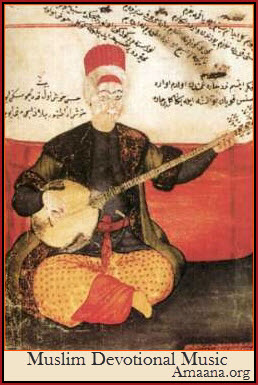

Such too is the structure of all those musical auditions which often, spontaneously, are improvised in Iran. The instrumentalist begins with a long prelude whose sonority continues to amplify. Then the human voice comes in, like a paroxysm, itself leading to deep sonorities, to culminate in turn in a paroxysm of feeling and gradually towards silence. And the postlude, with which the instrument accompanies that silence, seems at last to lose itself like the arpeggio of a far light, that light whose new dawn all mystics await.

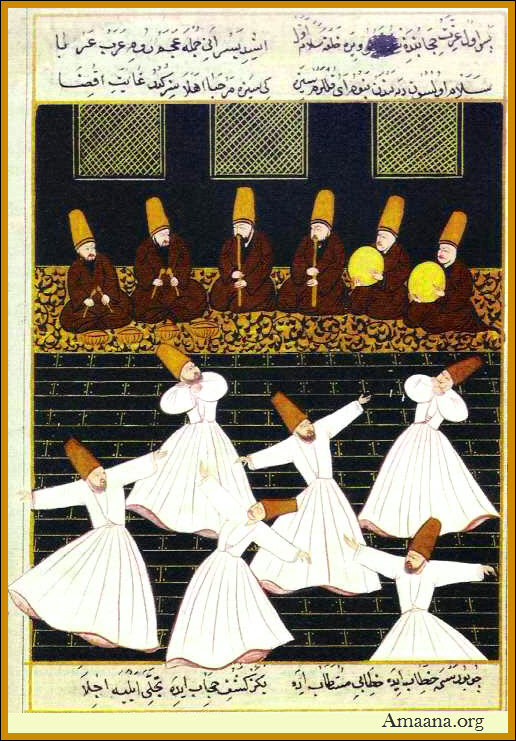

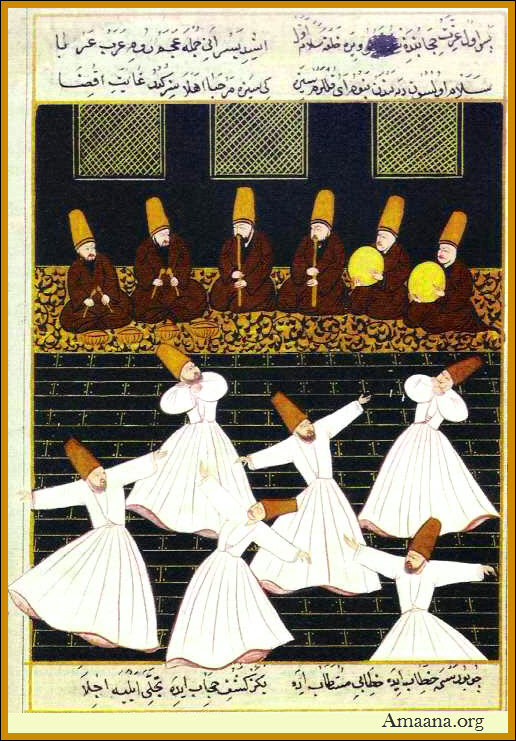

What is known as the Sama, the spiritual conceit, the

oratorio, of course goes beyond the special case of the Mowlana and its Order. The whole story of Iranian Sufism is before us, certain severe Masters (puritans that is to say) holding the spiritual concert in suspicion, while — others, by contrast, practice it with the assiduity of a cult, from which each retains an overwhelming impression. Among the latter I would cite one example, a great twelfth-century Master, Ruzbehan Baqli Shirazi, compatriot of

Hafez of Shiraz, whom he preceded by some two centuries and with whom he is linked by many affinities.

At the end of his life, however, we see Ruzbehan abstaining from the practice of listening to music: he no longer needed the intermediary of sensible sounds, the inaudible had become audible to him as a pure interior music. Thus his whole life exemplifies that structure of musical audition of which I have just spoken. To a friend who questioned him on the reason for his abstention, Shaykh Ruzbehan made this reply:

‘Henceforth it is God in person who gives me his concert (or God himself is the oratorio I hear). That is why I abstain from listening to anything other than He would make me hear (or any other concert than Himself).’ — Ruzbehan Baqli Shirazi

At the end of a lifetime’s experience, when the ear of the heart, of the interior man, becomes indifferent to sounds of the outer world, at that moment it perceives harmonies which can never be heard by the man dispersed outside himself, torn away from himself by ambitions of this world. What the ear of the heart then perceives are the harmonies of the music beyond the grave which certain privileged ones have already perceived even in this world, rendering that opaque barrier transparent for them.

At his death a friend and disciple of Shaykh Ruzbehan remained especially inconsolable. For years, every morning, at dawn, they had made it a habit to chant alternately verses of the Quran. Such was the grief of the lonely friend in Shiraz that he used to go and sit at the head of the tomb and there to begin, alone, the chanting of the Quran. But one day, as dawn came, it came to pass that the voice of Ruzbehan made itself heard from the invisible, from one world to the other, or rather the two friends took up again, in the same interworld, the antiphonal chanting of the Quran. And so it continued each day, at dawn, until the friend confided in one of his acquaintances. ‘From that time,’ he said, ‘I no longer heard the voice of Ruzbehan.

This, as if to suggest that, if the mystic must sing in order to speak, if the meaning of the mystic is essentially musical, this meaning remains incommunicable. From the moment we have the temerity to communicate, to reveal the fugitive instant when ‘the soul becomes visible to the body’, then that secret is lost to us.

Therefore I wish to say no more. But I would hope, in conclusion, that this sacralization of music by Persian mysticism may help us to some presentiment of the meaning of a ‘beauty’ which arouses in the modern world a veritable fury of denial and destruction. I would hope that we may perceive the significance and the permanent presence of an art which is not a province of fashion. The work of a Mawlana, like that of a Ruzbehan and many more besides, which illustrates the spiritual history of Iran is, every time, essentially the expression of a personality whom we shall not find twice among men. To whoever, then, has truly understood, it will never occur to suppose that they have been ‘superceded’.

Henry Corbin (1903-1978) was a scholar, philosopher and theologian. He was a champion of the transformative power of the Imagination and of the transcendent reality of the individual in a world threatened by totalitarianisms of all kinds. One of the 20th century’s most prolific scholars of Islamic mysticism, Corbin was Professor of Islam & Islamic Philosophy at the Sorbonne in Paris and at the University of Teheran. He was a major figure at the Eranos Conferences in Switzerland. He introduced the concept of the mundus imaginalis into contemporary thought. His work has provided a foundation for archetypal psychology as developed by James Hillman and influenced countless poets and artists worldwide. But Corbin’s central project was to provide a framework for understanding the unity of the religions of the Book: Judaism, Christianity and Islam. His great work Alone with the Alone: Creative Imagination in the Sufism of Ibn ‘Arabi is a classic initiatory text of visionary spirituality that transcends the tragic divisions among the three great monotheisms. Corbin’s life was devoted to the struggle to free the religious imagination from fundamentalisms of every kind. His work marks a watershed in our understanding of the religions of the West and makes a profound contribution to the study of the place of the imagination in human life.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Related

On the Meaning of Music in Persian Mysticism

On the Meaning of Music in Persian Mysticism  Such too is the structure of all those musical auditions which often, spontaneously, are improvised in Iran. The instrumentalist begins with a long prelude whose sonority continues to amplify. Then the human voice comes in, like a paroxysm, itself leading to deep sonorities, to culminate in turn in a paroxysm of feeling and gradually towards silence. And the postlude, with which the instrument accompanies that silence, seems at last to lose itself like the arpeggio of a far light, that light whose new dawn all mystics await.

Such too is the structure of all those musical auditions which often, spontaneously, are improvised in Iran. The instrumentalist begins with a long prelude whose sonority continues to amplify. Then the human voice comes in, like a paroxysm, itself leading to deep sonorities, to culminate in turn in a paroxysm of feeling and gradually towards silence. And the postlude, with which the instrument accompanies that silence, seems at last to lose itself like the arpeggio of a far light, that light whose new dawn all mystics await. At his death a friend and disciple of Shaykh Ruzbehan remained especially inconsolable. For years, every morning, at dawn, they had made it a habit to chant alternately verses of the Quran. Such was the grief of the lonely friend in Shiraz that he used to go and sit at the head of the tomb and there to begin, alone, the chanting of the Quran. But one day, as dawn came, it came to pass that the voice of Ruzbehan made itself heard from the invisible, from one world to the other, or rather the two friends took up again, in the same interworld, the antiphonal chanting of the Quran. And so it continued each day, at dawn, until the friend confided in one of his acquaintances. ‘From that time,’ he said, ‘I no longer heard the voice of Ruzbehan.

At his death a friend and disciple of Shaykh Ruzbehan remained especially inconsolable. For years, every morning, at dawn, they had made it a habit to chant alternately verses of the Quran. Such was the grief of the lonely friend in Shiraz that he used to go and sit at the head of the tomb and there to begin, alone, the chanting of the Quran. But one day, as dawn came, it came to pass that the voice of Ruzbehan made itself heard from the invisible, from one world to the other, or rather the two friends took up again, in the same interworld, the antiphonal chanting of the Quran. And so it continued each day, at dawn, until the friend confided in one of his acquaintances. ‘From that time,’ he said, ‘I no longer heard the voice of Ruzbehan.