Miraj — The Prophet’s Ascension: To See the Face of God and Return to Humanity

Miraj — The Prophet’s Ascension: To See the Face of God and Return to Humanity

By Omid Safi

One of my friends undertook a lengthy and difficult journey this week, from Tennessee to Cincinnati, there to Frankfurt, to Istanbul, to Jordan, then a 14-hour wait at a checkpoint, before arriving in Jerusalem. In Jerusalem he headed straight for the Aqsa mosque at 3 a.m.

Why would a person spend close to 70 hours getting from Tennessee to a small mosque in an occupied section of Jerusalem? After all, isn’t God everywhere? To answer that question is to understand how Muslims are not merely monotheists, but devotees of the One God who seek to follow through the path of Muhammad to meet God face to face.

This week is a special one for Muslims, one in which we celebrate the most potential spiritual paradigm in Islam: the Prophet Muhammad’s ascension to meet God face to face, and the choice to return home so that other beings can have their own ascension.

From Mecca to Jerusalem, and Meeting With the Prophets

The beginning of the Prophet’s ascension narrative start out quite ordinary: Muhammad had gone back to the Ka’ba to perform the night time prayer. He loved the solitude and peaceful nature of the Ka’ba at nighttime, and often used it as a time and place of retreat. This night, though, he would be visited by the angel Gabriel, who was to be his companion on an extra-ordinary journey. However, rather than being a straight journey “heavenward” from Mecca, as it were, the journey first goes to Jerusalem. Thus before the heavenly ascension proper (mi’raj) from Jerusalem to Heaven, there is first the night journey (isra) where Muhammad is taken from Mecca to Jerusalem. The isra emphasizes the commonality of the revelations of Muhammad, Jesus and Moses, thus reiterating the sanctity of all Abrahamic faiths. It was Jerusalem that served as the first direction of prayer for Muslims, before the decision to change to Mecca. The choice of Jerusalem as the initial site, as well as the ultimate redirection to Mecca indicates both the shared origin of Islam as part of the Abrahamic family as well as its own particularity.

The isra is alluded to in the Quran in the following narratives:

“Glory to the one who took his servant on a night journey from the sacred place of prayer to the furthest place of prayer upon which we have sent down our blessing, that we might show him some of our signs” (Quran 17:1).

The “sacred place of prayer” (masjid al-haram) is the vicinity of the Ka’ba, whereas “the furthest place of prayer” (masjid al-aqsa) is the famed Al-Aqsa Mosque, today situated adjacent to the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem. This narrative connects together Mecca as the city of the Ka’ba, built by Abraham and renovated by Muhammad, to Jerusalem, the biblical city of King Solomon, and the land where Jesus walked.

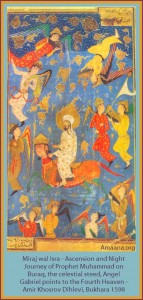

The journey from Ka’ba to Jerusalem became one of the favorites of Muslim artists, who often depicted Muhammad riding what can only be described as an angel-horse (buraq).

Direct Encounter With God

Jerusalem would not be the destination of Muhammad’s journey, but rather the Lord of Jerusalem, the Lord of Mecca, and the Lord of all the worlds. In the Quranic narrative, we get another passage that identifies the broad outline of this zenith of Muhammad’s heavenly ascension where Muhammad encounters God directly.

By the star when it sets

Your companion has not gone astray nor is he deluded

He does not speak out of desire

It is nothing less than an inspiration inspired

Taught to him by one of great power

And strength that stretched out over

While on the highest horizon.

Then drew near and descended

At a distance of two bows’ lengths or nearer

He revealed in his servant what he revealed

(Quran 53:1-10)

This passage, simultaneously vibrant and veiled, has captured the spiritual imagination of Muslims for more than 1,000 years. The narrative here, like a great Hitchcock mystery, works precisely by allowing the imagination of the audience to supply the details. Indeed, its appeal is through leaving things suggested, indeed unsaid. The combination of saying, unsaying and imagination provides an inviting context in which the reader is not just reading words on a page, they are participating in the production of the meaning. In the passage, the phrase “Your companion” clearly refers to Muhammad: It is affirmed that Muhammad is not going astray, and that the words do not arise out of Muhammad’s desires or delusions. Then the picture becomes elliptical and mysterious. In response to this mystery, Muslims have offered variant opinions regarding the precise meaning of these verses. These different opinions tell us a great deal about how different Muslims have come to conceptualize the relationship not just between God and Muhammad, but indeed between God and humanity. To appreciate these differences, we will take on a close reading of these verses.

What we know from the verse is that Muhammad has been taught by “One of great power” who sends down the inspiration (wahy) to Muhammad. But who is this mysterious character? Is it God? Is it Gabriel? Does it make a difference in the meaning of the episode? The difference is as great as the difference between God and angels. Muslims have imagined the identity of the unnamed character, one simply identified as “One of great power” differently, and that difference tells us a great deal about their assumption vis-à-vis God and humanity. A dominant tradition has been to state that the unnamed character is in fact Gabriel, since Gabriel is the angel of revelation. According to this reading, Muhammad is said to have had a vision of Gabriel during his spiritual journey. This type of a narrative has appealed to those Muslims who theologically like for God to remain God and humanity to remain humanity — with the twain never meeting. It has, for example, been a way for many theologians and rationalists in Islam to interpret this passage.

Yet other Muslims have read the same narrative, and imagined this encounter in powerfully different ways. These are the Muslims who yearn for nothing less than seeing the very face of God. For them, the one “Mighty in power” who teaches the Quran is none other than God. In this reading of the Qur’an — equally plausible through the rules of Arabic grammar — Muhammad has a face-to-face encounter with the Divine. What is more, if Muhammad ascended to God, if it is indeed possible to have a direct encounter with God, then that possibility is open to all of humanity. That possibility remains open to us. The Muslims who gravitate toward this reading of the ascension are usually known as the mystics (Sufis) of the Islamic community. For them, these narratives are not just about the time of Muhammad, but a description of reality even now: As it was then, so it is now. As with Muhammad, so with us. In fact, for these mystical Muslims the very model of a spiritual life becomes nothing short of first aspiring to and then (God-willing) attaining to a direct encounter with God.

This difference of interpretation also tells us a great deal about the ways in which these various groups of Muslims see and emulate Muhammad. All Muslims emulate the Prophet. It is in how the Prophet’s ascension is commemorated that different Muslims differentiate themselves. If Muhammad went to see God, then ordinary Muslims want to emulate the one who saw God. The mystics of Islam, on the other hand, want to follow Muhammad completely by stepping in his footsteps. Not being content to merely imitate Muhammad, they want to experience what Muhammad experienced, embody what he embodied. If Muhammad saw God, they want to see God. If Muhammad ascended to heaven, they want to ascend to heaven. There is a great commonality among all of these interpretations, namely the reverence for Muhammad who shows them the path toward God. The first group so reveres Muhammad that they believe he attained spiritual experiences — like direct encounter with God — that are not open to most human beings. The second group so reveres Muhammad that they wish for a Muhammadi encounter with God. Paradoxically, these mystics take following in Muhammad’s footsteps literally. Here is one of the intriguing aspects of a religious tradition in which God is revealed through a sacred language: mystical readings of scripture — and God — emerge not by going around the literal meaning, but by going through them. The literal meaning of scripture does not close off possibilities of deeper meaning — it leads to them.

Meeting God (or Gabriel) Face-to-Face

Almost every part of the passage became subject to further elaboration and unpacking. How close did Muhammad come to God/Gabriel? According to the narrative, it was “two bows’ lengths” (qab qawsayn). “Or Nearer” (aw adna). The commentaries that grow up around the verse first come to speculate on the meaning of the distance of “the bows’ length.” Those more theologically inclined who like to keep God and humanity at an arms’ length read the narrative as twice the distance that a bow can shoot an arrow, thus about a football field. Others read it as the length of two bows, that is, a few feet. Yet others, more mischievous, imagine a bow whose string has been pulled — as in the distance between the two ends of the bow, a few inches apart. What matters of course in the end is not, ever, the actual distance. It is rather the involvement of the human being in imagining increasing levels of intimacy between humanity and God.

And after books have been filled out describing this, after words have been exhausted — as the Qur an says, if the oceans were ink and trees were pen, the praise of our Lord could not be exhausted — in one short phrase the Quran points simultaneously to the limitation of language, and the invitation to dream more: “or nearer.” God — or Gabriel — came as close as two bows’ length (however that is understood), or nearer. This is what great literature has in common with scripture, with X-files and with Hitchcock: the power of suggestion. The Quran repeatedly warns humanity of baseless conjecture (zann) in attributing to God falsehood. Yet there is another type of imagination (khayal) that the tradition identifies as beatific, and as one that can lead humanity closer to God.

The concluding lines of this Quranic verse go on to state:

The heart did not lie in what it saw

Will you then dispute with him on his vision?

He saw him descending another time

At the lote tree of furthest limit

Therein was the garden of sanctuary

When there enveloped the tree what enveloped it

His gaze did not turn aside nor did it overreach

He had seen the signs of his lords, great signs.

(Quran 53:13-18)

Here again the mystery of the passage continues: Muhammad sees not with his eyes, but rather with his heart (fu’ad). The heart spoken of here is not merely the lumpy flesh in the chest, but the very throne of God’s spirit. Did God not reveal to Muhammad in a private communication that the “Heavens and the Earth do not contain me, but the heart of my faithful servant” does? Of all the human faculties, it is the heart that is most suitable for beholding the Divine. When humanity is created, God breathed into humanity something of Divine Spirit. As the Quran states in one of those rare and marvelous verses where God speaks in the first-person voice: wa nafakhtu fihi min ruhi — “I breathed into humanity something of My own Spirit” (Quran 38:72).

The spirit, whose seat is always the heart, is that in humanity which is from God, closest to God, and thus most suitable for perceiving and beholding the Divine.

And the Return to Humanity

As powerful as the narratives of ascension are, the grace for the community does not end with the ascension. To every ascent, there is a descent. While most Muslims focus on the experience of ascension, it is important to realize that there has to be grace in both ascension and in the return. The Quran is explicit in this, as the word most frequently chosen for “revelation” deals with the idea of being “sent down.” There is mercy in Muhammad being elevated to heaven, and there is mercy in the lowering down of the Word of God. Muhammad ascends to heaven, and has the direct Encounter with God. The question remains: Why return? If in that utmost position of bliss, why detach oneself from immediately beholding the Divine, and return to this realm?

The answer has to be connected to the same reason that this world was created: compassion. Like a Bodhisattva, who postpones his own entry into Nirvana, Muhammad returns from the awe-some mystical experience of being with God for the sake of his community. This selfless compassion, indeed sacrifice, is not one that most mere mortals would have chosen. Even a great 16th century Muslim saint of South Asia, ‘Abd Al-Quddus Gangohi, is remembered as having said: “I swear by God that if I had reached that point, I should never have returned.” And yet, thanks be to God, the Prophet returns. This too has remained a key part of Islamic life, that the true test of the women and men of God is not just to ascend, but to be able to return to humanity, to eat and sleep in the midst of the people, to conduct trade and human interaction, to live a family life — and yet for one moment to not become unmindful of the presence of the Ever-Merciful.

And so here we are as Muslims, still aspiring to ascend, still aspiring to see God face to face as the Prophet did, still aspiring to return transform. This is the point of the journey to Aqsa mosque in Jerusalem. This is the point of the 70-hour journey my friend undertook, and that is the point of prayer we all undertake. Prayer for Muslims in nothing other than rising to see God face to face, as did Muhammad. Come on bus, come on plane, come on prayer, we seek to rise like Muhammad.

So come, let us ascend.

So come, let us see the face of God.

And come, let us return to humanity, transformed, full of mercy, as the one who was sent as a mercy to all the worlds.

This essay has been adapted from Omid Safi’s biography of the Prophet Muhammad, titled Memories of Muhammad: Why the Prophet Matters. (HarperCollins, 2009).

Source: HuffPost